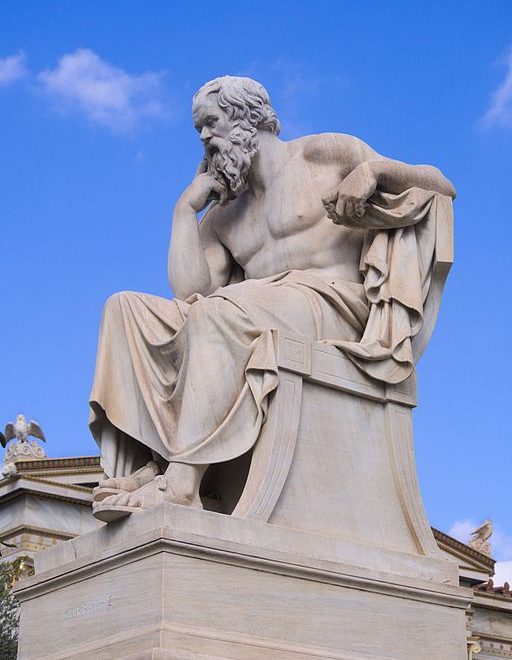

In my last article, The Flow of Thought, Part 7: Rediscovering Science as the Love of Wisdom, I made a case for the value of re-envisioning natural science as philosophy. While science might never come to mind today when philosophy is discussed, this was not always the case. The association of Solomon with the type of wisdom that includes nature lore provides a biblical example. Likewise, the great philosopher Socrates was mocked in his own day by the playwright Aristophanes for having his head in the clouds of speculation about the natural world. Although this claim was untrue—Socrates was almost exclusively concerned with the questions of moral philosophy or ethics, with some metaphysics thrown in—this very fact demonstrates the connection of philosophy with knowledge about nature.

Today the term ‘philosophy’ is almost synonymous with abstract questioning and skepticism; too often the modern discipline is construed as anything but practical—more likely to be concerned with whether or not we are in the matrix, or if words have any definite meaning at all, than how to live life in the here and now. As Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi mentions in his classic Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience:

“’Philosophy’ used to mean ‘love of wisdom,’ and people devoted their lives to it for that reason. Nowadays professional philosophers would be embarrassed to acknowledge so naïve a conception of their craft. Today a philosopher may be a specialist in deconstructionism or logical positivism, an expert in early Kant or late Hegel, an epistemologist or an existentialist, but don’t bother him with wisdom.” (138)

The specialization of modern philosophy has resulted in a focus on the obscure to the neglect of the tried and true. To be sure, deep and unanswerable questions are not new to the philosophical tradition, but the workable wisdom of the tradition has too often gotten lost in abstruse reasonings.

Part of the problem with this development is that philosophy is neglected among the young: at our PreK-12 schools and in home education. Parents, teachers and curriculum planners have imbibed the assumption that philosophy is for college students. The unfortunate outcome is that few college students have been inspired with the love of wisdom that would make collegiate study of philosophy fruitful. But more than that, the moral reflection and wisdom necessary for life are absent from the time of life when they are most necessary to form character.

Of course, I know very well that philosophy was conceived of as the culmination of the liberal arts tradition. (Clark and Jain make a movement in the right direction by according it a place in 9th-11th grades in their paradigm; see The Liberal Arts Tradition, 2nd ed. Appendix VI, p. 287.) In the Roman period only after gaining mastery of the liberal arts of language and mathematics would a student proceed to Athens or some other school of philosophers to pursue the deepest questions. But this didn’t mean that philosophical questions were neglected along the way. And if we’re going to recapture the love of wisdom and restore the school of philosophers in our educational renaissance, we’re going to have to find ways to embody the issues and subject matter of moral philosophy more clearly in our pre-college teaching.

There are three clear steps to doing this that are more or less hinted at in our psychologist’s reflections on finding joy and fulfillment by getting into the flow of thought through amateur philosophy. They are 1) to recapture the vision of teachers and parents as amateur philosophers, 2) to embrace the humble path of wisdom, and 3) to avoid the trap of specialization by becoming philosophical generalists, approaching every subject from the perspective of moral philosophy.

Teachers as Philosophers

Our cultural conception of the ideal teacher is haunted by the ghost of amateur philosophers. Mr. Miyagi from the 1984 film The Karate Kid is a good example of this. While the character Daniel benefits from the domain knowledge and skill of Mr. Miyagi in karate, what he is really in need of is instruction in a way of life. Mr. Miyagi teaches him how to overcome obstacles and setbacks, by, for instance, repairing the damaged bicycle that Daniel had simply thrown into the dumpster. Even Mr. Miyagi’s famous trick of teaching Daniel karate blocks through household chores is just as much a moral and spiritual lesson about humbly accepting the necessity of work and submitting to elders or the tradition even when you don’t understand. And the heart of the movie turns on the acceptance of tragedy and grief through stoic and eastern conceptions of self-mastery.

This is just one example that could be multiplied many times, with the point being that our culture still has this dream of a philosopher-teacher whose role it is to guide us on a quasi-religious quest for wisdom and the good life. This fact owes something to Socrates and to stoics like Epictetus, but also to many others in a great tradition of philosophical schools down through the centuries.

But in the modern educational system the possibility for teachers to take on this role has been all but crowded out through the domain-specific siloing of teachers into prescribed time-windows and the competing conception of teachers as professional bureaucrats who dare not venture into the personal lives and values of their students. (To be sure, if my children were attending a government school, I’m not sure I would want just anybody trying to play Mr. Miyagi for them….)

In the late 19th and early 20th century Charlotte Mason expressed a similar critique, except that she feared that a focus on cramming content into students was undercutting the teacher-philosopher approach. She felt that her philosophy of “living books” tested immediately by narration went a substantial way toward avoiding this problem:

“The teacher who allows his scholars the freedom of the city of books is at liberty to be their guide, philosopher and friend; and is no longer the mere instrument of forcible intellectual feeding.” (vol. 6 p. 32)

The logic here is that when a teacher is too focused on forcing content into the minds of students, he or she is not able to focus on being the philosophical mentor that the student needs. Since the practice of narration helps to ensure that content is being assimilated well, the teacher is free to all but ignore that and focus on the deeper questions, the moral and intellectual habits of the student, and where next to point the student in their journey toward wisdom.

This dovetails well with the problem of specialization mentioned earlier. Our psychologist’s goal is, of course, to make us all amateur philosophers, and so his encouragements are particularly helpful to us as teachers, as we consider taking up Mr. Miyagi’s mantle:

“Amateur philosophers, unlike their professional counterparts at universities, need not worry about historical struggles for prominence among competing schools, the politics of journals, and the personal jealousies of scholars. They can keep their minds on the basic questions.” (138)

Teachers at PK-12 schools and home educators should view themselves as amateur philosophers and focus on the big picture and the basic questions of philosophy. We should major on the majors, especially because we have the freedom to do so, but also because it’s what our students need at this stage in their development. And while natural philosophy and metaphysics have an important place, moral philosophy is the beating heart of an education centered on the formation of character or the development of virtue. Therefore moral philosophy should be pursued with an appropriate passion, as Socrates did, focusing on almost nothing else.

The Humble Path of Wisdom

For some of us teachers and parents, this will mean going back to philosophical school ourselves, in the sense of dusting off that old philosophy textbook from college. Or, even better, we could pick up for the first time those philosophical classics the textbook references, like Xenophon’s Memorabilia or The Memorable Sayings of Socrates, any of Plato’s Dialogues, Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics, or Epictetus’ Enchiridion. If we’re going to approach our teaching with a philosophical spirit, we have to catch the bug somewhere. It’s best to embrace that humble path of wisdom-seeking for ourselves and learn to revel in it. As our psychologist comments,

“Again, the importance of personally taking control of the direction of learning from the very first steps cannot be stressed enough. If a person feels coerced to read a certain book, to follow a given course because that is supposed to be the way to do it, learning will go against the grain. But if the decision is to take that same rout because of an inner feeling of rightness, the learning will be relatively effortless and enjoyable.” (139)

Of course, this is good advice if our goal is only attaining flow in the pursuit of wisdom for ourselves. However, one of the first principles of philosophy, or the love of wisdom, is that it cannot be merely self-referential in this way. Csikszentmihalyi has caught himself in a philosophical paradox here, recommending the modern dream of a light and easy path of pleasure.

Reading whatever I feel like doesn’t seem like the transcendent pursuit of wisdom. After all, “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” (Proverbs 9:10), and a sense of humility and submission to the tradition in the midst of and in spite of painful emotions is one of the first lessons we have to learn. Even Mr. Miyagi knew that…. (“Wax on… wax off.”)

Christ’s yoke may be easy and his burden light to the one who has taken it on himself (see Matt 11:30), but this is only so for the one who has taken up his cross to follow the master to the place of his own brutal execution. Even for Socrates, the love of wisdom was a “practice of death” (Phaedo 81a). So perhaps I should rather urge you to read philosophy not for flow and pleasure, but for pain and death, and because you must, not because you will want to. Such is the minimum commitment necessary of one who would be a philosopher-teacher.

The Philosophical Generalist

But reading in this way to become philosopher-guides, we do not therefore embrace the steep climb of the specialist. We may need to climb the steep hill of Parnassus, or of Sinai, or finally of Calvary, but that is a different thing. As our psychologist mentions, specialization has its pitfalls:

“While specialization is necessary to develop the complexity of any pattern of thought, the goals-ends relationship must always be kept clear: specialization is for the sake of thinking better, and not an end in itself. Unfortunately many serious thinkers devote all their mental effort to becoming well-known scholars, but in the meantime they forget their initial purpose in scholarship.” (139)

We can be content to be generalists, especially if we can zero in on wisdom as the goal, rather than even the enjoyment of the pursuit of wisdom, which after all is a rather strange self-referential circle that our secular psychologist is unwittingly leading us into.

Part of the reason he feels he must do this is because of the splintering of moral philosophy into the social sciences (like psychology) in the first place. In The Liberal Arts Tradition (2nd ed) Clark and Jain tell of the quest of the modern social sciences, like psychology, ethics or economics, to unmoor themselves from the unproven assumptions of traditional moral philosophy:

“The contemporary social sciences… often attempt to study aspects of man in isolation from one another without reference to man as a whole person in society pursuing happiness in and through his relationships. They also tend to ignore the central question of how virtue and meaning in life contribute to human happiness…. The methodologies of the contemporary social sciences implicitly critique traditional moral philosophy by suggesting it relies on assumptions about human nature and human purpose that are not rationally or empirically verifiable.” (132)

Our psychologist feels the need to justify recommending philosophical study merely on the basis of its potential for entering the flow state—an empirically verifiable method of increasing positive emotion. And since we all know positive emotions are a good thing, in a value-less world, he can recommend it to us without breaking our taboos (ironically) of radical individualism, since the positivity of positive emotions is a lowest common denominator value that we can all get on board with.

Of course, one of the reasons that we have been able to go as far with Csikszentmihalyi as we have in this series is that he stands within the new positive psychology movement, which is itself a revival of the virtue tradition of moral philosophy. In fact, Clark and Jain commend Martin Seligman, a founder of the positive psychology movement for how he “has powerfully and successfully unmasked the assumptions of the old therapy model and defended a return to the notions of eudaimonia [happiness or human flourishing], virtue, and the pursuit of meaning in life” (158); he “recognizes that there is a moral nature to human persons and that the social scientists have to recall lost categories such as responsibility, will, character, and virtue” (160).

My readers will have no trouble embracing such concepts, embedded as they are within a Christian worldview. But we can still feel intimidated away from employing these concepts and questions in our teaching. Especially if we’ve received some higher-level academic training, we may have been indoctrinated into the reigning social science dogma that aims to keep philosophy at bay.

When teaching history, for instance, we’re more inclined to focus on insuring proper delivery of content and the mastery of facts. We tend to avoid discussion of the virtue or vice of figures, why certain courses of action were right or wrong, and the questions of proper relationships or the purpose of government. In literature classes, we focus on questions of technique and artistry, authorial background and narrative trivia, to the neglect of the central moral dilemma of the book.

The example of Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi should encourage us to embrace the perspective of moral philosophy in our teaching of any subject, but especially in the humanities. Where are you on your journey in the love of wisdom? Let’s restore the philosophical school in our hearts, our homes, and our PK-12 classrooms.

Previous articles in this series, The Flow of Thought

Part 1: Training the Attention for Happiness’ Sake; Part 2: The Joy of Memory; Part 3: Narration as Flow; Part 4: The Seven Liberal Arts as Mental Games; Part 5: The Play of Words; Part 6: Becoming Amateur Historians; Part 7: Rediscovering Science as the Love of Wisdom.

Final installment: Part 9, The Lifelong Love of Learning.

Leave a Reply