Onlookers viewing the reconstruction of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris might experience something similar to what onlookers in the 1200s had when the original construction of Notre Dame was still underway. Having begun in 1163, it was not completed until 1345. The site of its construction rests upon an island in the middle of the Seine. Crossing the Seine, one can make their way to the Latin Quarter, where one finds the medieval University of Paris. The Rue Saint-Jacques cuts through the Latin Quarter, aiming at Notre Dame on Seine. It was the street Thomas Aquinas daily walked upon, as he took up residence in the Dominican priory of St. Jacques when he was appointed regent master of theology at the University of Paris in 1256.

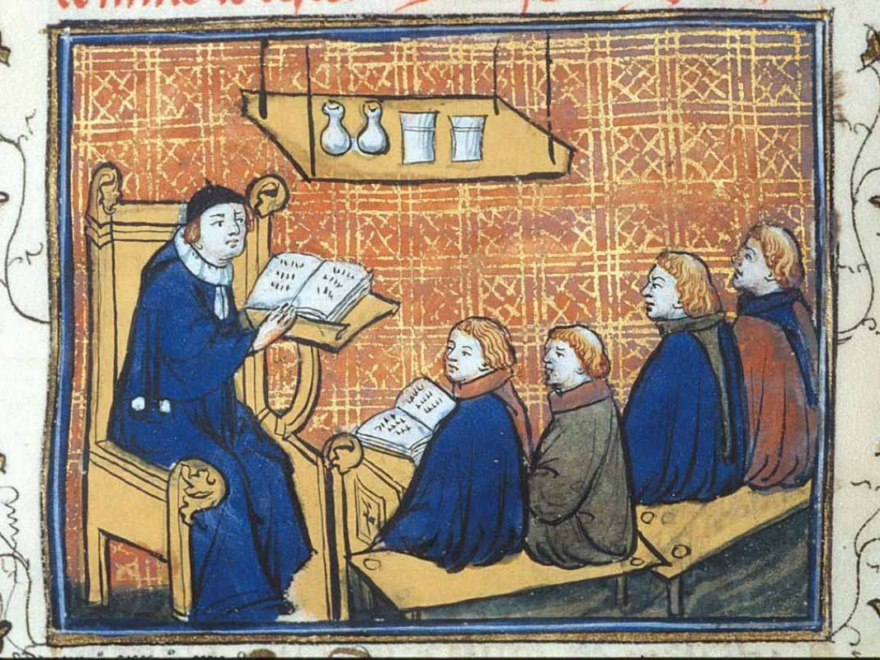

Of all the medieval universities, Paris was pre-eminent. The University of Paris attracted scholars from every country, in large part due to the immense reputation it accrued due to previous esteemed professors such as William of Champeaux, Peter Abelard and Peter Lombard. So many students flocked to the university, that housing was scarce. Boarders could exact exorbitant rates of the young scholars, making this the education of the wealthy aristocracy. Thus, Thomas living at the priory was not only down to his religious commitment to his Dominican Order, but also presented an affordable residence with an easy commute.

At the outset of his appointment at the university, Thomas was required to present inaugural lectures that expounded a biblical text. This was known as the principia biblica, one of two lectures at the inauguration of a new professor. The passage Thomas chose for this brief lecture was Psalm 104:13. The story goes that he received this passage in a dream where a figure handed him this particular text. However we regard this legend, it seems that Thomas worked out a rather compelling delineation of the relationship between religious knowledge and the instruction of students in the liberal arts. In many respects, this brief lecture anticipates the fuller synthesis Thomas achieved in his career, reconciling faith and reason. This article explores his inaugural lecture, entitled “Rigans montes,” to draw from it insights for our own educational renewal movement.

An Exposition of Rigans Montes

The text of the inaugural lectures was lost for centuries until they were discovered again in 1912 among the writings of Remigio dei Girolami at Santa Maria Novella in Florence, according to Ralph McInerny, who translated the text for the Penguin edition (Selected Writings 5). One can find the text online or in its published form in McInerny’s edited volume, Thomas Aquinas: Selected Writings. It’s a rather brief sermon that falls into four parts following a short preface. The sermon is an exposition of Psalm 104:13 which reads “You water the hills from your upper rooms, the earth is sated with the fruit of your works.” (Note: in the Vulgate the numbering of the Psalter differs from our English versions, so in printed editions of Thomas’s lecture, one will find it referring to Psalm 103:13.) For Aquinas, this text serves as a model for how divine revelation reaches the mind of the learner.

He seems quite Platonic when he reasons that the “gifts of Providence” are given to those who are lower “by intermediaries” in his preface. The water cycle becomes a metaphor for this intermediation. The clouds release rain at the top of the mountain. This water flows down the mountain, feeding the rivers, which go out into the land “so that the satiated earth can bear fruit.” By analogy, divine wisdom flows down through well-trained minds to those who are learners. He writes, “Similarly, from the heights of divine wisdom the minds of the learned, represented by the mountains, are watered, by whose ministry the light of divine wisdom reached to the minds of those who listen” (Selected Writings 12). This then structures the four parts of his sermon, so that his outline covers the height of doctrine, the dignity of teachers, the condition of learners, and the order of communication. Let us follow this outline.

To begin, divine wisdom comes from on high. Thomas references James 3:15 regarding how God’s wisdom comes from above. He acknowledges how some things are generally known. So, for instance, knowledge of God’s existence is naturally known by all. Some divine knowledge is comprehensible, such that Paul can state in Romans 1:19, “what can be known about God is plain to them,” that is all humanity. But some divine knowledge is hidden or veiled, requiring revelation through Scripture and the inworking of the Holy Spirit. Ultimately, God reveals this high wisdom in order that “you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name” (John 20:31). And for those who are in Christ, Paul’s admonition is that we would “seek the things that are above” (Col. 3:1). So, Thomas begins his exposition by accumulating a variety of text to make the point that divine wisdom is high and exalted, yet God pours this wisdom out in various ways such that it flows down the mountain, so to speak.

Because of the height of divine wisdom, teachers who would teach divine wisdom must have certain characteristics. Thomas begins by calling upon teachers to despise earthly things and cling exclusively to heavenly things. He quotes Philippians 3:20 where Paul writes that our citizenship is in heaven. The vocation of the teacher is a high calling. Next, the teacher must be illumined by divine wisdom. Returning to the image of the mountain, it is the top of the mountain that receives the first light of the sun in the morning. For Thomas, the teacher receives these high beams of light. He writes, “the teachers are illumined by the first beams of divine wisdom” (Selected Writings 14). Then, Thomas continues the analogy of the mountain, this time focusing on how a mountain provides protection to the land, a defensible position. The teacher of divine wisdom defends the faith and stands against error. He sees these characteristics exemplified in Paul, who defines his own ministry in these terms:

“To me, though I am the very least of all the saints, this grace was given, to preach to the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ, and to bring to light for everyone what is the plan of the mystery hidden for ages in God who created all things.”

Ephesians 3:8-9

To express this a different way, a teacher ought to be enthralled and experience joy in being able to reach for the heights of wisdom, while also being grateful and humbled to be a vessel to convey this exalted knowledge to others. Such dispositions place the teacher in right frame of mind to climb the mountain and bring these truths down to the land below.

Learners also ought to have dispositions that make them capable of receiving divine knowledge. Chief among the dispositions is humility. To receive something so high, one must recognize how low one is. The student is of the earth in the analogy of the mountain. The knowledge comes down from on high. And like the earth, the student must acknowledge this lowness by remaining humble. Yet, like the earth, the student must also be characterized by firmness and fruitfulness. When we think about training students in a biblical worldview – or imparting divine wisdom to them – the goal is to establish them firmly in their faith as well as to enable them to experience fruit in their lives.

Thomas concludes his reflections by addressing the mode of communication. Even though God communicates his wisdom abundantly, the teacher cannot know everything and, likewise, the teacher cannot even teach everything he has come to know. Teaching is limited because we are limited beings. We know in part and we teach in part, with the hope that our insufficiency is empowered by God’s sufficiency. Thomas goes on to convey that teaching is an act of sharing in wisdom. The teacher does not possess the wisdom. Wisdom belongs to God, who shares abundantly with us. So the teacher draws the learner into this stream of shared wisdom. Because wisdom belongs to God, the power of God is required in order for it to be properly conveyed or communicated.

Reflecting on the Nature of Teaching and Learning

The mountain analogy expressed at the outset of his career is not quite his full expression of the harmony of all knowledge in his Summa Theologica. What this inaugural lecture does, though, is remind us of some key principles that are worth reflecting on.

First, the matter we get to work with as teachers is high and weighty. The dictum that “all truth is God’s truth” means that no matter the subject area, there is a pathway from the heights of the mountain top to the topic at hand. The truths handed down through the generations arrive in our classrooms on a daily basis. To engage with this material is to stand on holy ground, to open oneself to the mysteries of the cosmos and the depths of the human spirit. This is no small task. The work before us is worthy, but also demanding. We must approach it with reverence and humility, for the insights we seek to impart to our students have the power to inspire and transform. Before our students can engage with such wisdom, we ourselves must be captivated by it. Let us delve into these rich veins of knowledge, that we might emerge enlightened and empowered.

Second, in fulfilling our calling as teachers, it is easy to become weighed down by the demands of the classroom and the deadlines of the calendar. We can lose sight of the joy and wonder that first drew us to this calling. However, it is essential that we cultivate these qualities within ourselves, not just for our own fulfillment, but for the sake of the wisdom God has bestowed from the heights of heaven. There comes a point when Latin grammar or geometric proofs become mundane. And it is exactly at this point where we must ask of God to renew our curiosity and wonder. True joy and wonder can only be found when we humble ourselves and depend on God’s power working through us. It is not something we can manufacture on our own, but rather a gift that comes from surrendering our own agenda and allowing the Holy Spirit to work. As we learn to walk in this posture of humility and dependence, we will find a renewed sense of awe and excitement about the privilege of shaping young minds and hearts by means of the materials at hand. Our students will be the ones who reap the rewards, as they are inspired by teachers who radiate the joy of the Lord.

Finally, in our pursuit to teach students within this educational renewal movement, we must not lose sight of the true objectives to provide a firm foundation for our students to stand upon, and to cultivate fruitfulness in their lives. At the heart of this endeavor lies the timeless virtues of truth, goodness, and beauty. It is our responsibility to guide our students on a journey of discovering the profound truths that are foundational to life’s meaning, and to inspire them to live lives of moral integrity and excellence. Ultimately, the greatest gift we can impart to our students is the opportunity to walk in step with the Lord and to be discipled in the ways of the our Savior. For it is only through this intimate relationship that they will find the strength, wisdom, and purpose to thrive and make a lasting impact in this world. Let us, therefore, remain steadfast in our commitment to nurturing the whole person of each student so that they are well equipped with the tools they need to stand firm upon the ground of truth and to live fruitfully as they walk with the Lord.

Learn more about training and consultation packages that focus on improving your academic program.

Visit our consultation page for more information.

Leave a Reply