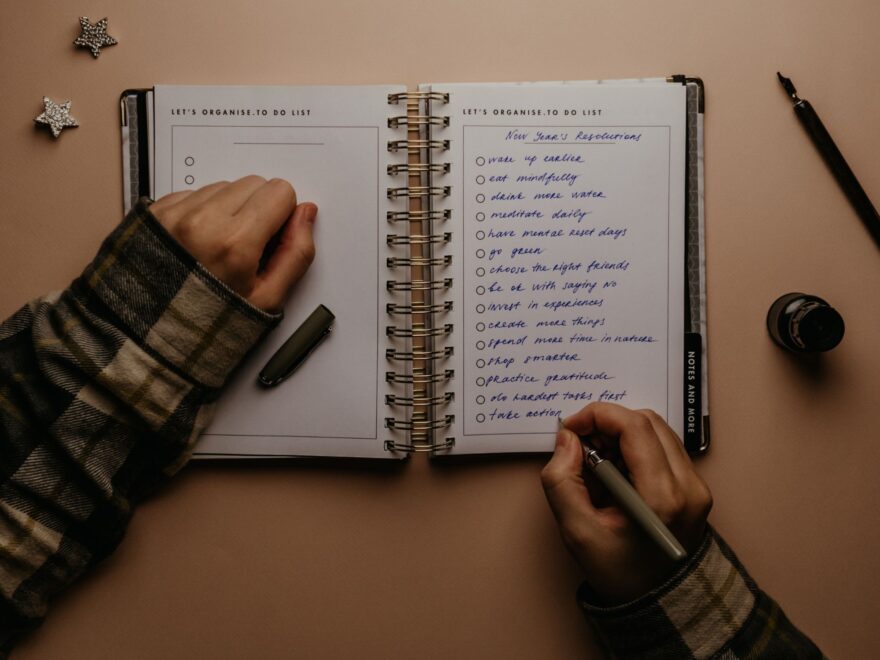

The idea of New Year’s resolutions elicits strong reactions from some people. “If you want to change, why wait until the New Year to start?” the cynical say. Others perhaps remember the failure of last year with some measure of shame and regret. Still others are fired up about the success and dream-fulfillment that lie ahead, given their newfound will-power and determination. According to some statistics almost half of American adults participate in New Year’s resolutions, and most relate to improving one’s health (see 19 Surprising New Year’s Resolution Statistics (2024 Updated) (insideoutmastery.com)). Unfortunately, only 9% stick with their resolutions, leading some to suppose that the whole thing is just a waste of time, amounting to no more than another marketing gimmick.

Of course, not all resolutions are created equal. There’s a resolution to get in shape by working out more, and then there are The Resolutions of Jonathan Edwards, full of profound thought and purposeful Christian spirituality. Are written goals and resolutions classical? Should personal goal setting be a deliberate feature in our educational programs? I believe the answer to both questions is yes. There is a rich classical tradition of personal goal setting, especially as it relates to virtue and habit development. Helping our students cast a positive vision for their own personal growth and detail the steps they can take toward their own development is a powerful and undervalued lever in the classical, Christian educator’s hands.

Classical Goal Setting

To demonstrate that resolutions and goal setting are classical, we need look no further than the Stoic philosophers. Their handbooks and meditations are full of the stuff of resolutions. Classical goal setting might be said to differ from many modern New Year’s resolutions in its overarching focus on character as the outcome rather than money, beauty or career. Living a good life, developing areté or virtue, and serving God and neighbor better should be the aim of a classical and Christian set of resolutions. This is in contrast to goals centered merely on increased discipline to promote personal fulfillment.

At the same time, even goals with a narrow focus tend to work, or at least substantially increase the likelihood that a person will hit their goal. The reason why is articulated well by Aristotle. It is as simple and profound as saying that those who have a clear target are much more likely to hit it:

If, then, there is some end of the things we do, which we desire for its own sake (everything else being desired for the sake of this), and if we do not choose everything for the sake of something else (for at that rate the process would go on to infinity, so that our desire would be empty and vain), clearly this must be the good and the chief good. Will not the knowledge of it, then, have a great influence on life? Shall we not, like archers who have a mark to aim at, be more likely to hit upon what is right? If so, we must try in outline at least, to determine what it is, and of which of the sciences or capacities it is the object.

Aristotle, Ethics and Poetics (Veritas Press: 2019), 10

Aristotle believes the chief good is eudaimonia, happiness or, we might say, personal fulfillment. We have already had occasion to modify Aristotle’s endorsement of happiness to suit the transcendent frame of a Christian worldview in the opening foray into a series on Aristotle’s intellectual virtues (see “Aristotle’s Virtue Theory and a Christian Purpose of Education”). We can merely note for our purposes here that Aristotle’s metaphor of archers having a goal or target is incredibly helpful.

In life we all make choices. In fact, we all deliberate about what is good for ourselves. Having in mind the ultimate goal that we are aiming at will necessarily clarify the mechanics involved in taking a successful shot. Of course, here Aristotle is showing how our life is not an infinite regression of goods that are merely useful for some other good. Classical goal setting does not settle for the immediate desired end but pushes its participants to ask why. Why do you want to go to the gym? Why do you want to be more physically fit? Why do you want to have more energy and vibrancy as well as look better? For Aristotle, these questions lead up and out to his big picture vision of eudaimonia and the good life.

This questioning and clarification process helps sort our immediate wants from bigger goals and our future vision. It also makes classical goal setting more effective, because in the process we are also sorting out our various priorities and connecting our short term goals and objectives to our ultimate telos and vision of human flourishing. The clarity achieved will then increase motivation to stick to a new habit or practice in spite of obstacles. If our goals are connected to a lesser vision, which, say, identifies human pleasure as the end-all-be-all, the misguided vision of happiness that Aristotle says most human beings operate with, then we will be easily led astray from our goal of regular exercise when the pain increases and the Siren song of some other pleasure is calling our name (read Educating for Self-Control, Part 1: A Lost Christian Virtue).

Modern Research on Goal Setting

Similarly modern research has shown that there are better and worse ways to set goals. Brian Johnson explains the importance of imagining both a positive future vision and the presence of obstacles to making that vision a reality. He draws from the research of Rick Snyder in his book The Psychology of Hope to detail the need for not only goals, but a sense of agency and multiple pathways (i.e. plans B, C, D, etc.) to get there (Areté: Activate Your Heroic Potential, Heroic Blackstone: 2023; 88-89). Genuine hope distinguishes itself from mere wish by involving both a sense that I can personally contribute in some way toward a better future and the realism that struggle, failure and the need to try-try-again will be part of that process.

Johnson also draws from the work of Gabriele Oettingen to much the same effect (90-91). In her book Rethinking Positive Thinking Oettingen uses the acronym WOOP to delineate the most effective set of steps to turn resolutions into reality: Wish, Outcome, Obstacles, Plan. Each step should be written down and articulated. A wish for the future must be connected to the overall purpose or vision of the good life (think Aristotle’s eudaimonia). Obstacles must be anticipated with some plans or “implementation intentions” for how to deal with them. This process helps us stick to the vision when the rubber of good intentions meets the road of reality.

Jordan Peterson, the now famous Canadian Psychologist and author of 12 Rules for Life, has independently worked out something similar in the form of his Future Authoring program:

Dr. Jordan B. Peterson, professor of Psychology at the University of Toronto, decided to ask his students to sit down and write about their ideal future. They were asked to specifically describe the type of person they wanted to be, the skills they wanted to attain, and the relationships they wanted to have, among other things. (see Self Authoring – Future Authoring)

Notice that writing out the “ideal future” constitutes the major element in this process. From public lectures we know that Peterson’s Future Authoring program also involves imagining a negative picture as well of what the hellish version of the self would be if it went down a dark path instead.

(Read Patrick’s series on Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life: Rules for Schools?, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.)

In addition, like the work of Snyder and Oettingen, Peterson’s process also involves getting down into the nitty gritty of daily habits and potential obstacles. It also has the support of research studies to demonstrate its effectiveness (see Self Authoring – Research). For instance, a single intensive goal setting session significantly improved the GPA of undergraduate students who were struggling academically within a semester (see Hirsh and Peterson, “Setting, Elaborating, and Reflecting on Personal Goals Improves Academic Performance,” 260). The research is clear, despite the low success rate of New Year’s resolutions. Goal setting in a detailed way with written goals and articulated obstacles has been shown to be incredibly effective.

Applying Goal Setting to Education

The study cited above makes the application of goal setting to education obvious in one sense. It can be used powerfully as an intervention for students who are struggling academically. This should not be overlooked in our K-12 classical Christian schools and homeschools. Too often we resort to lecturing a student about what they should do or not do in order to improve their academic performance. Part of why this does not work is because it doesn’t appropriately harness a student’s autonomy or will, in Charlotte Mason’s terms.

Sometimes we are tempted to think of habit training as something we do to a student, rather than something we do with a student. But Charlotte Mason is clear that a student must own his or her own character development, otherwise it is a mere veneer:

We who teach should make it clear to ourselves that our aim in education is less conduct than character; conduct may be arrived at, as we have seen, by indirect routes, but it is of value to the world only as it has its source in character…. What we do with the will we describe as voluntary. What we do without the conscious action of will is involuntary. The will has only one mode of action, its function is to ‘choose,’ and with every choice we make we grow in force of character. (vol. 6, p. 129)

A goal setting process allows an individual student to make their own assessment of their future vision, their obstacles, and the pathways forward. The student then choses to follow the positive goals that they set for themselves. The voluntary and personal nature of this process make it ideal for developing character.

Now we must add in to this process the classical goal setting features we discussed before. We should direct them in their resolutions not just toward improving academic performance or an exercising habit but their ultimate purpose from a Christian perspective and how their immediate goals relate not only to their personal fulfillment but also to the glory of God and their salvation in Christ. Christian classical goal setting should not only WOOP (Wish-Outcome-Obstacles-Plan), it should do it Jonathan Edwards style.

What does this look like in our education settings? The first and most obvious note is that a classical goal setting exercise should most likely not be an assignment with a grade. The tang of artificiality and forced reflection might undercut the autonomy and will of the student. It is important to have times and seasons set apart perhaps at the start of the year and the beginning of a new quarter or semester, or even a unit in a course, where students are given the opportunity to reflect in writing on their own learning and progress, as well as their ultimate goals and personal growth. I have conducted a writing session similar to the future authoring prompts for students during an Upper School student orientation time. Students were told that what they wrote would not be collected or graded and were encouraged to reflect seriously and purposefully on their own future vision of themselves and their goals for the year.

In some classes and courses, specific virtues and vices can be used as prompts or options to articulate their own assessment of themselves. The classical and Christian content of history, literature and biblical texts can be helpfully applied in a meditation journal, where students regularly react personally to questions that ask them to apply the examples and thoughts of these subjects to themselves. Most of all, we can conclude that the development of character and specifically the intellectual virtue of prudence or practical wisdom hinge on these sorts of practices. Prudence involves a person deliberating about the real decisions they are making on a daily basis in light of a future vision of flourishing. Goal setting and resolutions are necessary part of that process. In order to turn out men and women of prudence we should carve out periodic class time for intentional reflection regarding personal development.

A series entitled “Counsels of the Wise” explores and applies the intellectual virtue of prudence or practical wisdom (Greek: phronesis):

- Counsels of the Wise, Part 1: Foundations of Christian Prudence

- Counsels of the Wise, Part 2: Why Reviving Moral Philosophy Is Not Enough

- Counsels of the Wise, Part 3: The Practical Nature of Prudence

- Counsels of the Wise, Part 4: Preliminary Instruction in Prudence

- Counsels of the Wise, Part 5: Principles and Practice, Examples and Discipline

- Counsels of the Wise, Part 6: A Pedagogy of Prudence

- Counsels of the Wise, Part 7: Leadership, Liberal Arts, and Prudence

- Counsels of the Wise, Part 8: Aiming at the Intermediate or Aristotle’s Moral Virtues

Leave a Reply