In the previous article we finally laid out a pedagogy for training students in prudence. While there are many preliminary actions that we can take to sow the seeds of prudence and provide for students’ good instruction from sources of moral wisdom, it is nevertheless true that the full acquisition of practical wisdom awaits a student’s later years. In secondary and collegiate education, then, students should study the ethical dimensions of all subjects and be taught through dialectical and rhetorical means to reason about human goods using biblical moral categories.

If our educational renewal movement consistently graduated students well on their way to practical wisdom, that fact alone would entail a remarkable positive inheritance. I might go so far as to say that, even if our educational methods bore no better fruit in standardized test scores or excellent artistry in language, mathematics, or the fine and performing arts, still it all would have been worth it if our graduates were more prudent. Part of the reason for this is that no man is an island, and so, regardless of other attainments, the influence of these prudent citizens on the world at large is nothing short of incalculable. Prudence is the quintessential virtue of true leadership.

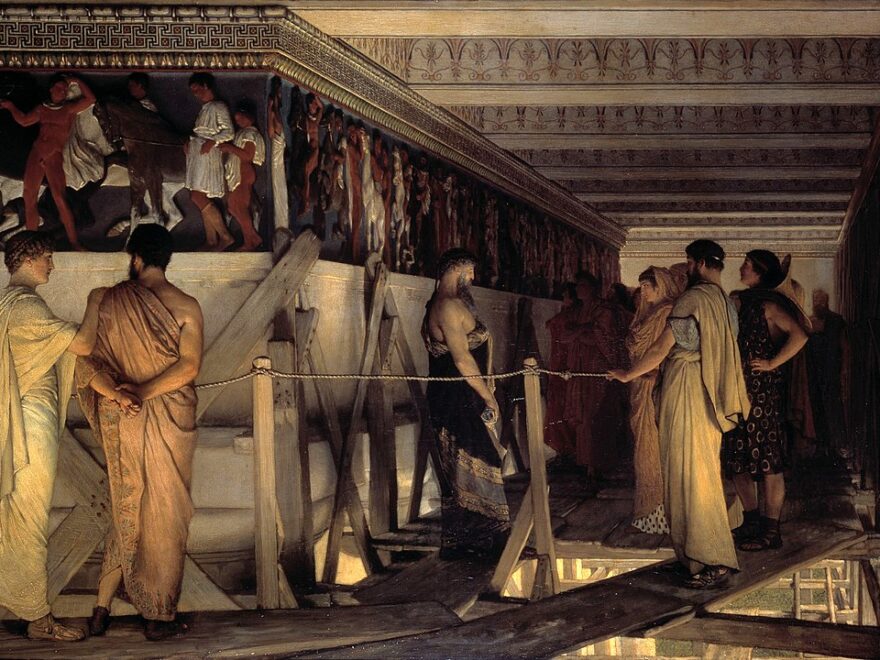

Much ink has been spilled on the liberal arts as the proper training for a free human being. A free society relies on men and women leaders who are able to reason persuasively with both verbal and mathematical precision, in order to lead us to human flourishing. As Aristotle asserts,

That is why we think Pericles and people of that sort to be practically wise–because they have theoretical knowledge of what is good for themselves and for human beings, and we think household-managers and politicians are like that. (Reeve, Aristotle on Practical Wisdom, 56; VI.5 translation)

In actual fact, it is not the liberal arts simply, but the liberal arts facing prudential matters that prepare a person for leadership. Study of the liberal arts can tend toward the arcane, mystic and purely academic. The best students of abstract intellectual matters are not always the best leaders.

Aristotle’s inclusion of both household-managers and politicians justifies our exploration of prudence as a leadership trait generally. When he says that “political wisdom and practical wisdom are the same state of mind, but to be them is not the same,” (VI.8, Revised Oxford Trans.) he further clarifies that political wisdom is that type of practical wisdom concerned with the city, just as economic or household management is that practical wisdom concerned with the household. This doesn’t negate the fact that a person could have individual practical wisdom but not the leadership varieties, because of lacking particular knowledge of that sphere. But it does mean that practical wisdom expands up into all types of leadership spheres, making the essence of practical wisdom itself highly desirable.

After all, our graduates will lead in various ways after their Christian classical education, whether it be as parents themselves, church and small group leaders, coaches, business managers and executives, and perhaps even politicians. Our world needs more prudent leaders, just as it does more prudent individuals.

In this article we will explore practical wisdom in dialogue with Jim Collin’s idea of Level 5 leadership from his book Good to Great. Then we will note some practical implications for training prudent leaders through the school experience today.

Level 5 Leadership and Prudence

In his masterfully researched Good to Great, Jim Collins and his team of researchers set out to discover what separated enduringly great businesses (measured “objectively” by publicly available stock valuation) from comparison companies. According to his own admission Collins “gave the research team explicit instructions to downplay the role of top executives so that [they] could avoid the simplistic ‘credit the leader’ or ‘blame the leader’ thinking common today.” In spite of this, the presence of what they came to call “Level 5 Leadership” in all the Good to Great companies at the time of transition kept staring them in the face, the more so since the traits they saw were so paradoxical and unexpected.

Collins describes the Level 5 executive as a person who “builds enduring greatness through a paradoxical blend of personal humility and professional will” (20). He goes on to describe it this way:

Level 5 leaders are a study in duality: modest and willful, humble and fearless. To quickly grasp this concept, think of United States President Abraham Lincoln (one of the few Level 5 presidents in United States history), who never let his ego get in the way of his primary ambition for the larger cause of an enduring great nation. Yet those who mistook Mr. Lincoln’s personal modesty, shy nature, and awkward manner as signs of weakness found themselves terribly mistaken, to the scale of 250,000 and 360,000 Union lives, including Lincoln’s own. (22)

Lincoln provides an inspiring example of this “professional will” combined with “personal humility.” These leaders are not the superstar executives that led the company to a brief period of high profitability during their tenure as CEO, but then left it in the lurch at their departure.

Collins lists a hierarchy of five levels of leadership that we can profitably set in dialogue with Aristotle’s intellectual virtue of prudence:

- Level 1 – Highly Capable Individual: Makes productive contributions through talent, knowledge, skills, and good work habits.

- Level 2 – Contributing Team Member: Contributes individual capabilities to the achievement of group objectives and works effectively with others in a group setting.

- Level 3 – Competent Manager: Organizes people and resources toward the effective and efficient pursuit of predetermined objectives.

- Level 4 – Effective Leader: Catalyzes commitment to and vigorous pursuit of a clear and compelling vision, stimulating higher performance standards.

- Level 5 – Level 5 Executive: Builds enduring greatness through a paradoxical blend of personal humility and professional will. (Jim Collins, Good to Great, 20)

First, the highly capable individual has established good habits or virtues that productively make use of the talent, skills and knowledge that he has. This individual level of prudence calculates correctly that it will be beneficial to himself to work well and be known as a good worker, as that will provide him with the good things of life.

Second, the contributing team member has what Aristotle calls “consideration” or “judgment” (gnome; see Nicomachean Ethics VI.11), discerning correctly what is fair in working together with a team. This fair-mindedness relies on a perception or comprehension of each person’s rights and responsibilities.

Third, the competent manager receives objectives or goals from and is able to use his cleverness (a morally neutral category related to practical wisdom in Aristotle; see VI.13) to organize people and resources toward meeting those goals. Moreover, this manager does so in a way that coordinates those combined efforts well and is in this sense political. We now see the forerunners of prudence approaching something like it in applied political leadership.

Fourth, the effective leader adds still another element of practical wisdom, in that the leader first perceives and then articulates “a clear and compelling vision”–something that Aristotle would have called understanding the proper ends or goals of human flourishing and then having the art of persuasion to communicate it to others. The effective leader not only has the cleverness to chart out a path to these goals, but discerns the end from the beginning because he has high standards of excellence (virtue) within himself that enable this perception.

Fifth, the level 5 leader adds on to these the crowning achievement of practical and political wisdom, because he has subsumed his own personal benefit within the good of the community or organization as a whole. Collins hesitates to use the term servant leadership because of how it might degenerate into mere niceness in our imaginations, but the conclusion is unavoidable:

Level 5 leaders channel their ego needs away from themselves and into the larger goal of building a great company. It’s not that Level 5 leaders have no ego or self-interest. Indeed, they are incredibly ambitious–but their ambition is first and foremost for the institution, not themselves. (21)

Christians should not be surprised by this finding, resonating as it does with the model of self-sacrificial leadership attested in scripture.

The sacrificial leadership described in Collins’s Good to Great also has a firmness of will, reminiscent of Charlotte Mason’s Way of the Will, which we have already had occasion to mention. The prudent leader may take time to deliberate well and correctly, but once his mind is made up about the best course of action, his will is iron. This iron will can coexist with a heart of humility partly because his knowledge is so firm and clear. He sincerely knows why, how and what is best for himself and others precisely because of his practical wisdom.

A Pathway for Prudent Leaders

There are several practical take-aways for Christian classical schools that accept prudence as one of their aims. The first comes from the possibility of taking these 5 levels as a scope & sequence of sorts for leadership development in our schools. It might be fair to criticize the value of group work and teamwork in class projects from the vantage point of simple academic attainments. But if, as we are contending, school should act as a training ground for prudent decision-making in life, then the back-and-forth negotiations and power dynamics of persons are possible life lessons in and of themselves. Mentoring students up the levels of leadership could function as one strand in the curriculum governing this type of learning activity.

It is worth pausing to note that it is important to differentiate this from simple rhetorical skill. Often in rhetorical training, it is the speech or paper that is graded or ranked, regardless of the rightness or wrongness of the viewpoint taken. This isolation of the simple product of persuasion makes sense when we are focusing on developing the art of rhetoric only, but if we expand the vision to prudent leadership, then we can see that the speech functions holistically within a vision & strategy, a web of relationships, a set of challenges, and a perception of the resources, needs, and trade-offs of various pathways. While real-life experience leading is the most accurate training ground for this, proxies involving actual leadership of other students can help.

It is for this reason that student leadership within a house system or student council can be a proper classical educational feature. Not because schools should function like democracies, but because of our educational goals. These leadership opportunities mimic real-world complexity than games or assignments since they involve real human beings and definite choices for their good or ill within a timeframe and constraints. Of course, if we were merely talking about strategy, it might be that our modern strategy games (whether board games, video games, or computer games) might afford the best training. Chess is a good example of this, originating as it did almost 1500 years ago in India, and its venerable history of mimicking military tactics. A little bit of such things throughout youth might be of value to future prudent leader, but because all the particulars of an actual leadership situation matter, becoming a grandmaster will be unlikely to transfer to level 5 leadership.

In fact, this case helps to illustrate one of the key differences between artistic training and an education for prudence. While artistry of any sort benefits from an abundance of focused practice within the discipline, game, or subject matter, too much specialization might actually be a hindrance to prudent leadership. As David Epstein illustrates in his book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, a wide array of experiences often equips us with a better intuition, vision, and creativity for making decisions in the complex situations we face.

In this sense too, the liberal arts were made for prudence, not only because they prepare a person with practical skills to lead (writing, discussing, speaking, calculation, charting, etc.), but also because they help us encounter the world in all its variety and prevent us from focusing too narrowly on one subject or aspect of things. Prudent leaders are generalists, who have encountered the world in all its complexity: people, products, research, and relationships, to name just a few aspects. They draw from all this varied data to make complex calculations about the best course of action and they regularly lead others to human goods.

Let’s smooth this liberal arts pathway with lessons for level 5 leadership at our schools.

Leave a Reply