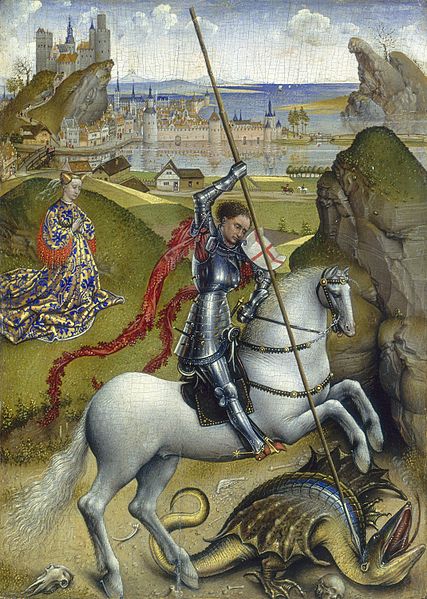

The story of Saint George and the Dragon is a classic tale of courage and faith. It tells the story of a brave knight, George, who saves a princess from being sacrificed to a dragon that has been terrorizing a small town. After slaying the dragon, George is celebrated as a hero and his bravery is rewarded with the hand of the princess in marriage. The story has been adapted into many different versions throughout history, but its core message remains the same: courage and faith can overcome any obstacle.

There’s a lovely edition of Saint George and the Dragon written by Margaret Hodges and illustrated by Trina Schart Hyman that is an excellent book for young readers or reading aloud as a family. It is a retelling of the famous rendition of the story in Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene. A story that connected Saint George to English royalty. With the coronation of King Charles III this weekend, we will see many symbolic representations of Saint George as he has been venerated as the patron saint of England since the Middle Ages. From the England’s Saint George flag (red cross on white background) to the stained glass window in the nave of Westminster Abbey depicting George fighting the dragon, there are emblems that keep alive the memory and significance of Saint George today.

We see the story of Saint George appear frequently under different names. Take, for instance, the story of Harry Potter saving Ginny Weasley from the Basilisk in the second novel in the Harry Potter series. Here Potter plays the heroic Saint George role. This interpretation has been posited by Jordan Peterson. He writes:

“She [Ginny] is the maiden—or the anima, the soul—forever incarcerated by the dragon, as in the tale of St. George. It is up to Harry, orphaned hero, to wake and rescue her.”

Jordan Peterson, Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life (Random House, 2021), 79.

Peterson has been an important intellectual voice raising our attention of Carl Jung, an individual who provides a wealth of insight into the heroic individual. Viewing the heroic stories of figures such as Harry Potter, Bilbo Baggins and Saint George, Peterson sees how the heroic archetype emanates from the ultimate heroic figure: Jesus Christ. Peterson writes:

“In the desert, Christ encounters Satan (see Luke 4:1-13 and Matthew 4:1-11). This story has a clear psychological meaning—a metaphorical meaning—in addition to whatever else materials and metaphysical alike it might signify. It means that Christ is forever He who determines to take personal responsibility for the full depth of human depravity. It means that Christ is eternally He who is willing to confront and deeply consider and risk the temptations posed by the most malevolent elements of human nature. It means that Christ is always he who is willing to confront evil.”

Jordan Peterson, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos (Random House, 2018), 180.

It is important to note that Peterson, a clinical psychologist and professor of psychology, has interpreted this passage from a psychological standpoint. He leaves open a more theological understanding of these passages and the nature of Christ. For this reason, we can see how Peterson’s psychological read of Christ is not in conflict with the theological conviction that Christ dies for sins as an atonement.

Having brought up Saint George, the dragon and Jordan Peterson, we are well situated to understand the relevance of Carl Jung to literature, history, mythology, psychology and philosophy. In this article we will explore Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious and how it plays out in archetypes we see in narratives, myths and dreams. Once we have a good grasp of Jung’s framework, we can then consider what role Charlotte Mason’s method of narration might play relative to this framework.

Jung and the Collective Unconscious

Carl Jung (1875-1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. He is best known for his theories of the collective unconscious, archetypes, and the psychological complex. His work has had a profound influence on modern psychology and psychiatry, as well as on philosophy, anthropology, literature, and religious studies. A protégé of Freud, he later broke away from his

Jung first presented his theory of the collective unconscious to the public through his essay “The Concept of the Collective Unconscious,” published in 1936. He begins his definition by differentiating the collective from the personal unconscious. He writes:

“While the personal unconscious is made up essentially of contents which have at one time been conscious but which have disappeared from consciousness through having been forgotten or repressed, the contents of the collective unconscious have never been in consciousness, and therefore have never been individually acquired, but owe their existence exclusively to heredity.”

The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 9.1 (Princeton University Press, 1969), par. 88.

So, the personal unconscious can be understood as a storehouse of material that was once conscious for the individual. But the collective unconscious was never any individual’s personal consciousness. Jung goes on to state:

“In addition to our immediate consciousness, which is of a thoroughly personal nature . . . there exists a second psychic system of a collective, universal, and impersonal nature which is identical in all individuals. This collective unconscious does not develop individually but is inherited. It consists of pre-existent forms, the archetypes.”

The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 9.1 (Princeton University Press, 1969), par. 90.

To be clear, individuals experience this collective unconsciousness but it does not reside in any individual, but is a shared set of forms that Jung calls “archetypes.” Jung first studied this concept by analyzing the dreams of patients, a practice his predecessor Freud had likewise analyzed. As such, one of the primary methods deployed by Jung to identify archetypes of the collective unconscious was to analyze dreams. And while this method can be both fascinating and productive, I want to quickly move on to other avenues of study pursued by Jung. By this I mean the archetypes found in mythology and fairy tales. Jung writes in his essay “Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious”:

“Another well-known expression of the archetypes is myth and fairytale. But here too we are dealing with forms that have received a specific stamp and have been handed down through long periods of time.”

The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 9.1 (Princeton University Press, 1969), par. 6.

What this means is that archetypes have a mythological character that appear over and over again in literature and artwork. This is exactly what we see in the story of Saint George and the Dragon, a mythological archetype that gets re-packaged over and over again in literature under new guises—such as Harry Potter and Luke Skywalker—but connect to something heroic in human potential. We see this spelled out in detail in a stunning passage from one of Jung’s last works Mysterium Conjunctionis:

“In myths the hero is the one who conquers the dragon, not the one who is devoured by it. And yet both have to deal with the same dragon. Also, he is no hero who never met the dragon, or who, if he once saw it, declared afterwards that he saw nothing. Equally, only one who has risked the fight with the dragon and is not overcome by it wins the hoard, the “treasure hard to attain.” He alone has a genuine claim to self-confidence, for he has faced the dark ground of his self and thereby has gained himself. This experience gives him faith and trust, the pistis in the ability of the self to sustain him, for everything that menaced him from inside he has made his own. He has acquired the right to believe that he will be able to overcome all future threats by the same means.”

The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 14 (Princeton University Press, 1970), par. 756.

For Jung, the dragon resides within and must be confronted in order for the individual to truly know oneself and valiantly face the trials of life. One might be tempted to hear in this a form of self-realization that runs counter to faith in Christ for salvation; for Jung plays up the “faith and trust” in self. And while we must recognize that Jung was not friendly to the Christian faith, he saw how many of his concepts were actually grounded in Christian ideas. For instance, he identifies how the concept of archetype relates to the Imago Dei. One the subject of archetypes, he marshals evidence from both Irenaeus and Augustine to show how God has placed these archetypes of his divine nature within us. (see The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 9.1 (Princeton University Press, 1969), par. 5.)

To express this all succinctly, what Jung posits is that our imaginative enterprises from ancient myths to modern literature express something deep within us that connects to a transcendent reality. The more we understand particularly the heroic archetype, the more capable we are as individuals to encounter the chaos of our world and the struggles we confront within. To put it another way, the ancient quest for happiness or eudaimonia is the hero’s journey for which we are best equipped by reading and assimilating this heroic pattern from the great works.

A Note on Jungian Interpretation of Literature

Reading literature in light of Jungian archetypes can be both enlightening and fun. I have introduced Jung to high school students in my Modern World Humanities class. It can be eye opening to see beloved characters from in a new light. Take, for instance, a few characters from the Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. We have a complex of characters that are archetypal. Victor Frankenstein is a tragic hero who we see leaving the home, pursuing new avenues of scientific discovery, and then needing to protect his one true love from the monster he created. Victor’s father is the wise old man, giving sage advice at various points to Victor. Elizabeth Lavenza is at various points the damsel in distress and the nurturing mother. And the monster is the villain that the hero must confront to protect the damsel in distress. Seeing these characters in this light adds meaning to our reading of the text and can bring insight into the message of the novel.

Furthermore, there can be productive discussion about Jung’s concept of the shadow self. Jung describes the shadow as a dark part of one’s inner self that must be confronted to become a whole person. He writes:

“But if we are able to see our own shadow and can bear knowing about it, then a small part of the problem has already been solved: we have at least brought up the personal unconscious. The shadow is a living part of the personality and therefore wants to live with it in some form. It cannot be argued out of existence or rationalized into harmlessness.”

The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 9.1 (Princeton University Press, 1969), par. 44.

In the case of Victor Frankenstein, the monster represents his shadow self. He must confront that shadow and attempt to reconcile himself with it. Returning to the narrative of Saint Peter, we could then say that the dragon is not only an external force that must be confronted, but the dragon resides within. There is something profoundly Christian about this insight that residing within all of us is the villain we must heroically confront. And yet we are incapable of defeating the dragon apart from the help which God provides in Christ. I hear echoes Luther’s famous dictum simil justus et peccator “at once justified and a sinner.”

For Jung, literary criticism only played a small part of his understanding of the collective unconscious and the interpretation of archetypes. Yet he produced a brilliant essay on the matter written in 1922 entitled “On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry.” In this he looks not only at poetry but at all forms of art as a means of expressing the collective unconscious for that era. He writes:

“The artist seizes on this image, and in raising it from deepest unconsciousness he brings it into relation with conscious values, thereby transforming it until it can be accepted by the minds of his contemporaries according to their powers.”

The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Vol. 15 (Princeton University Press, 1971), par. 83.

By “this image” Jung means something primordial or ancient in nature that wells up within the artist from this collective unconscious into a specified consciousness through the artist. We might refer to this as the artist’s muse to capture the idea using more classical language. When we are analyzing artwork, we are really getting at the message of the piece and how it communicates not only to the specific context in which it arose, but if it has enduring value, then also the transcendent values that still speak to us today.

We must be careful not to collapse all readings of literature and art into a reduction of Jung’s archetypes, a tendency all too easy to follow when we first learn of the archetypes. Dawson comments on this tendency:

“Take a text. Read the surface narrative. Stamp an archetypal pattern on to it. Assume its significance. Indulge in some woolly generalization. Case closed.”

Terence Dawson, “Literary Criticism and Analytical Psychology” in The Cambridge Companion to Jung (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 286.

The temptation is to hear only one story repeated over and over instead of hearing how the great metanarrative becomes expressed in unique detail and complexity generating insights that cannot be generalized. So, while I highly recommend reading literature with Jungian archetypes in mind, do so with the caution that such a method helpfully unlocks the potential meaning of the text rather than making all texts say exactly the same thing.

The Assimilation of the Heroic

Thus far I have focused almost entirely on Jung and now I must introduce him to another character, Charlotte Mason (1842-1923). Or perhaps I should say I should introduce Mason to Jung, for she precedes him by a generation. It is clear that Mason was deeply interested in psychology as each of her six volumes on education refer to the subject in some manner. She shows an astonishing awareness of figures in America and Germany, with William James (1842-1910), Johann Herbart (1776-1841) and Friedrich Fröbel (1782-1852) featuring prominently. She shows know awareness of the Vienna School inasmuch as no references to Freud or Jung are to be found in her writings. (A piece with some references to Freud was commissioned for the The Parents’ Review written by Sir Maurice Chaig entitled “Some Aspects of Education and Training in Relation to Mental Disorder” and was published in 1924, one year after Mason’s death).

Mason shows herself to be competent if not groundbreaking as it relates to the field of psychology, especially as it relates to childhood development and learning theory. It should be noted that her forward thinking about neuroplasticity—a term she never used but referred to with phrases like “a mark upon the brain substance” (vol 6, 100)—was eventually validated almost 100 years later through neurological studies as recently as the 1990s. I mention all this to indicate that it does not seem to be a stretch to consider Mason’s writings on educational philosophy highly compatible with the roughly contemporaneous works emerging in the field of psychoanalysis on the continent during her lifetime.

Much could be made regarding the psychological significance of her philosophy of education, especially concepts such as viewing children as whole persons or training children in habits. What I want to dig into though from a psychological perspective is narration. While this might seem a wholly academic process, I contend that it has psychological significance in light of Jung’s insights about the collective unconscious. To that end, let’s explore some of Mason’s thoughts as it regards the impact narration has on children.

We begin by understanding how narration is fundamentally about assimilation and not memorization. Central to Mason’s method of narration is cultivating the child’s power of attention to be properly deployed on living texts. She writes:

“He will find that in the act of narrating every power of his mind comes into play, that points and bearings which he had not observed are brought out; that the whole is visualized and brought into relief in an extraordinary way; in fact, that scene or argument has become a part of his personal experience; he knows, he has assimilated what he has read.”

Charlotte Mason, A Philosophy of Education (Living Book Press, 2017), 16.

Narration, then, bring the full power of the mind into contact with the rich details of the text, enlivening the imagination to picture or visualize the scene at hand. Note how she recognizes that this power of attention assimilates something into the child’s personal experience. By reading something like Saint George and the Dragon, the child assimilates that narration into himself as though it was a personal experience. That child becomes well practices in the heroic encounter with the forces of evil. She differentiates this from memorization, which lack this power of assimilation.

“This is not memory work. In order to memorise, we repeat over and over a passage or a series of points or names with the aid of such clues as we can invent; we do memorise a string of facts or words, and the new possession serves its purpose for a time, but it is not assimilated; its purpose being served, we know it no more.”

Charlotte Mason, A Philosophy of Education (Living Book Press, 2017), 16.

There is a place for memory work, not doubt, but it cannot bring into the character and development of the child with the same force as narration. This helps us understand an intangible aspect of narration. When we narrate, the goal is not to somehow quickly memorize the text in order to tell it back. Instead, the goal is to powerfully visualize the text, to take it into oneself so that the telling back is actually to share something that is becoming very personal to the reader. This personalization process entails an emotional and aesthetic quality that we as educators must be mindful to cultivate as students grow in the art of narrating.

Mason advises us to be rather choosy about the books we place before our young readers. we are to guide them away from “twaddle” (Vol 1, 176) and bring them into contact with “living books” (Vol 6, 154). She views what we read as the food of the mind. It feasts on ideas. And so our reading should be full of living ideas. As we grow healthiest with nutrient dense foods, so our reading should be dense with these living ideas. We are not merely interested in giving them intellectual power, we must also present to our children living books that cultivate their character, their duty, and their industriousness. She writes, “The great tales of the heroic age find their way to children’s hearts.” (Vol 6, 181) So, the prerequisite to narration having the outcome of plugging into the collective unconscious that Jung elaborates is to curate a wide array of living books from “a liberal range of subjects.” (Vol 6, 156)

This process of narration cultivates the wellbeing of children with the goal that children grow to have what Mason describes as “unity” and a healthy relationship of “oneself with oneself.” This links up nicely with the Jungian sense that the heroic encounter with dragons is an internal process of encountering the darkest parts of ourselves. Mason recognizes that her method has a psychological effect for children. She writes:

“They are curiously vitalised; not bored, not all alive in the playing-field and dull and inert in the schoolroom. . . . There is unity in their lives; they are not two persons, one with their play-fellows and quite other with their teachers and elders; but frank, fresh, showing keen interest in whatever comes in their way.”

Charlotte Mason, School Education (Living Books Press, 2017), 62-63.

How often have we seen students taking on different personality traits in different contexts? Mason contends that schooling that enables children to have an encounter with living ideas promotes the kind of unity of character that enables them to be the same person wherever they find themselves.

Ultimately, it is the internal battle we must enable our students to fight with valor. Mason in her volume The Formation of Character envisions this internal struggle. She writes:

“Modern scientists have added a great deal to the sum of available knowledge which should bear on the conduct of those relations of oneself with oneself which are implied in the terms, self-management, self-control, self-respect, self-love, self-help, self-abnegation, and so on. This knowledge is the more important because our power to conduct our relations with other people depends upon our power of conducting our relations with ourselves. Every man carries in his own person the key to human nature, and, in proportion as we are able to use this key, we shall be tolerant, gentle, helpful, wise and reverent.”

Charlotte Mason, The Formation of Character (Living Books Press, 2017), 86.

This encounter with the self is fundamental to individual wellbeing. And, as she notes, only when we have truly reconciled accounts internally can we conduct ourselves masterfully with the external world.

Hopefully this walk through Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious and Mason’s method of narration has stimulated your thoughts on educational philosophy. One of the reasons I have elaborated this particular connection is to prepare myself to speak on this topic at the Charlotte Mason Centenary Conference in Ambleside, England this summer. I am honored to present at one of the expert panels on day 3 of the conference. There is a profound sense of privilege to walk the town where she spent a significant portion of her life a century after her passing.

Leave a Reply