In this week’s blog post I am going back into the vault to share with you a paper I presented at the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting in Atlanta on November 20, 2010. This was a pivotal moment in my career, having earned my PhD and taught for a few years at colleges and seminaries in the US and UK. I joined the faculty of Clapham School in 2009 and there first encountered Charlotte Mason. My introduction to Miss Mason’s philosophy of education completely revolutionized my teaching, and this was something I wanted to share with my biblical studies colleagues.

My assumption is that most followers of Educational Renaissance work within K-12 schools, but I suspect there are some who like me also teach in undergraduate or postgraduate settings either as adjunct faculty or full professors. My hope is that there will be a growing number of college and seminary professors who take seriously the craft of teaching and the concern to provide students the optimal learning environments. I offer this paper for your consideration that perhaps Miss Mason will help you transform your lecture hall into a place where students engage rich texts, assimilate through narration and plumb the depths of great ideas through discussion.

Introduction

The problem facing higher education today is not a crisis of information, or even knowledge, but a crisis of thinking well. Our culture has a glut of information readily available at any number of URLs. The passivity with which we access these things has led to a passivity of the mind; minds disengaged from the living ideas which transcend mere knowledge or information and which alone can give sustenance to the human organ best suited to face the complexities of our modern life.

My musings on today’s educational crisis, particularly as it relates to academic biblical studies, has benefitted greatly from reconsidering a model of education from an unlikely source. Charlotte Mason taught, led an educational reform movement, and produced six volumes on educational philosophy around the turn of the twentieth century. How can this educational philosophy address the concerns we have today as educators within the guild of biblical studies? This paper will explore her philosophy with a view to relating it to the biblical studies classroom. Her method of instruction offers exciting possibilities for utilizing the rich texts available to us—both ancient and modern—within our field and for drawing students into a mind-to-mind encounter with texts in such a way that students may grow in their capacity to think great thoughts.

Charlotte Mason

Charlotte Mason was born in 1842 an only child in Bangor, Wales. Her philosophy of education was prompted by her experiences teaching in Worthing, England and later at the Bishop Otter College in Chichester. Beginning around age 40 and spanning over three decades, Mason wrote six volumes dedicated to expounding her philosophy of education. These volumes capture her struggle to find an educational philosophy that transcends the class barriers that divided Victorian England. The surprising results of her method were seen in the successes of youth from mining communities, previously regarded as hopeless bastions of the uneducated working class. Her final volume, Towards a Philosophy of Education, published in 1923—the year she passed away—shows her development of thought as the Great War shattered the assumptions about culture and society that reigned in the 19th century.

During her lifetime, a movement of educational reform grew up around her teachings. The Parents’ National Educational Union (PNEU) was formed in 1886 to advance Mason’s philosophy of education among parents who were dissatisfied with the state of education in England. A number of Union schools were opened which carried out her philosophy. Shortly thereafter, a periodical was issued called Parents’ Review—a title reflecting the basis of her philosophy in the role of parents. This journal drew upon a wide array of voices who were working through various aspects of Mason’s philosophy and its practical implications. In 1892, a college dedicated to training teachers was opened in Ambleside, England. The school remains to this day a part of the University of Cumbria.

Three Elements of Mason’s Educational Philosophy

From the writings of Charlotte Mason—a person who devoted her life not just to teaching but to thinking about teaching—several worthy principles may be distilled. Mason understood education to comprise three tools. First, education consists of an atmosphere. This has to do not only with the physical appearance of the setting in which study is to occur, but also to the intangible quality of the space where students are enthused to learn. Teachers are to think intentionally about how the room is arranged, what is in the room, and what is not; all with the goal of creating an atmosphere conducive to learning. The most significant aspect, especially for those of us who have little control over the look and feel of the rooms to which we are assigned, is the atmosphere we establish through our presence and what we say as educators.

Second, education consists in the disciplined training of students in order to attend to the tasks not simply of academic enterprise but of a life devoted to personal growth. Some college students come to us with well-formed academic habits, but it is largely the case that students these days simply do not know how to accomplish simple tasks, such as memorizing Greek vocabulary, writing multi-paragraph essays with clearly articulated topic sentences, or even scheduling their reading load appropriately. We could add to these basic operational skills intellectual habits such as courage or humility. If we as educators don’t take responsibility for these shortfalls, then the higher-order projects we might have them do will not rise to the level we could otherwise expect from them. So, in my teaching, I actually spend time talking about the habits students need to have to succeed in university and these need to be reviewed consistently.

Finally, Charlotte Mason proposed that education consists in living ideas. If we are presented with “mere dry summaries of facts,” our minds will at some point flush these out of the system. Instead, if we are presented with living ideas from great literature, our minds are challenged to think along the same paths as the text, causing them to grow in maturity and sophistication. It is this point that has revolutionized my own teaching methodology, and I will spend the rest of my paper spelling out the method Charlotte Mason has formed for accessing these living ideas.

The Approach to Accessing Ideas in the Text

Mason articulated a five-part methodology that has been the foundation of my own educational praxis, although I cannot claim to have achieved mastery of it yet. First, one must provide students with “a well-chosen book”. For biblical studies, we have available to us not only the books of the canon, but literature from the Ancient Near East, the pseudepigraphical literature, the writings of early Judaism, the early church and even Greco-Roman materials. Furthermore, we are not limited to texts from the ancient world. A well-written book by a recent author can be an excellent guide to great ideas.

Second, the teacher should provide a brief talk before each lesson. This amounts to a lecture in our parlance. But, it is a lecture that is far more pared down than what I used to prepare. My goal now is to set up the student’s reading in such a way that they are introduced to primary issues that will give them success in reading the assigned lesson. In this brief lecture, I can feel free to bring up any number of complex issues. But I need to do so as a means to giving tools to the students. I’m thinking here of models of interpretation, historical background, social setting, exegetical conundrums, the composition history of a text, the outline of a book. My shift in thinking, though, has been to shift my work away from being the primary conveyer of content and toward enabling students to do the primary work of learning through direct contact with texts.

Third, students read their lesson. We literally read texts out loud in the classroom. I usually select passages from their out-of-class readings. I call on individual names, and there are a few who struggle with their reading diction. My goal is to have students encounter the ancient text as much as possible. Therefore, the focus of our class time is on texts. I find that, although this is a simple activity, the students attend closely to the reading and I get far fewer eyes glazed over, even in my three-hour evening class.

Fourth, students narrate or re-tell what was read. This is the most important step of the method. This is where students are able to assimilate their readings into their own knowledge. They are forced to think along with the text. Mason responds to the criticism that this is mere memorization by explaining, “in the act of narrating every power of [the] mind comes into play, that points and bearings which he had not observed are brought out; that the whole is visualized and brought into relief in an extraordinary way; in fact, that scene or argument has become a part of his personal experience; he knows, he has assimilated what he has read. This is not memory work. In order to memorize, we repeat over and over a passage or a series of points or names with the aid of such clues as we can invent.” She goes on to identify the role of memory work within the broader scope of education. But memorization is not assimilation. This component of Mason’s educational philosophy, I find, has been the tool that opens up for students a world of thought previously untapped.

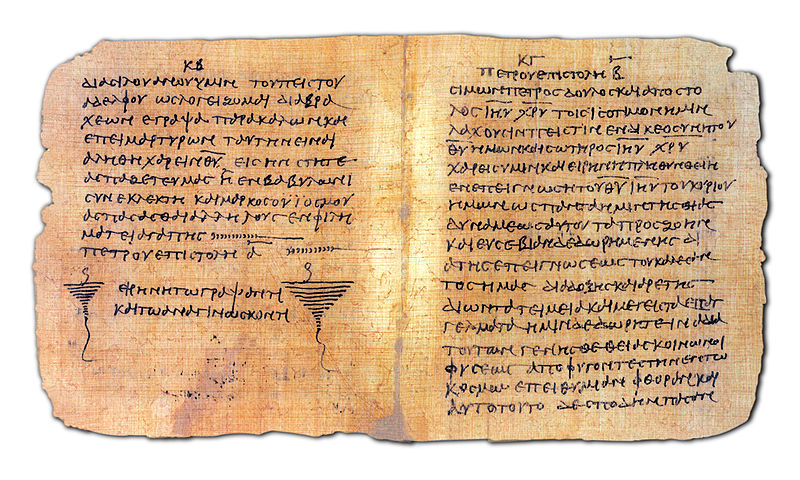

and the beginning of 2 Peter

Finally, the fifth part of the method is a concluding talk. Most often, this is a discussion about the text or reading. I facilitate this by asking leading questions, but more times than not, there is a student-to-student conversation that grows out of points they are noticing in the text. Sometimes I need to instruct students in the course of this discussion or, rarely, in place of the discussion. For instance, if we have read a text that is central to a model of interpretation, I might need to talk briefly about the background of, say, the German school that gave rise to the model of interpretation, critiques of it, and so forth and so on. What I avoid is collapsing the method so that the students become passive. If the ancillary ideas are so important, they might require their own session in which I will identify a text and apply the approach to it.

This is the method, then. It begins with the selection of an excellent text, rich with ideas. A small talk sets up the reading. We read the text (either aloud together or prior to the class). After reading, the students are called upon to re-tell the reading in their own words, supplying details from the text, in the proper order and capturing the language and style of the author. Finally, we talk about the text in a rich way that engages the ideas of the text.

The Method in Practice

I have applied this basic method with success in the coursework I teach at Trinity Christian College in Palos Heights, Illinois. Let me now spell out a couple of ways in which I have incorporated this method into an otherwise standard liberal arts Christian college. (Editor’s note: since writing this, I have also utilized this method at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Chicago and Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis.)

First, for each class session I prepare a lecture that will run roughly ten to fifteen minutes of a fifty-minute block. If the class time is longer, I still tend not to lecture for more than fifteen minutes since I would rather have the students engaged in the exercise of reading, narrating and discussing. I plan readings that must be done prior to class, just like most other professors do. However, I ask students to tell me in their own words the contents of that reading. This might take about five to ten minutes; maybe longer if the readings generate questions and discussion. I usually choose a passage from scripture that becomes the focus text for our class session. Sometimes I might cue up several scripture passages. I call on students to read aloud. When this is done, I call on other students to re-tell the reading. After this, I ask them, “What strikes you about this passage?” or “What did you notice about the passage?” or “What is this passage communicating?” There are any number of questions that can get students to think through the reading and begin discussing it.

Sometimes, a passage will have difficulties or raise problems in the minds of some students. I will allow this problem to be expressed and fester for a bit. I don’t want to step right in as the answer man. I want them to begin working through why there’s a problem here, what the factors are, what alternative interpretations might be there, etc. There is often a lot of back-and-forth between students as they grapple with these things. When the discussion begins to slacken, I will now go up to the board and ask students to call out the salient items under discussion, which I write down so that we can all visualize the ground we have covered. Only then, after having them work a long way through the matter, will I step in to assist them in bringing some kind of resolution. Sometimes, though, I might be able to leave them in suspense and have them do some light research along with a brief write-up on it. The energy behind the problem discussed in class supplies the energy that will motivate them to get it done.

One time, for example, I used the introductory lecture to teach my students about call narratives and the elements that scholars have discerned as the constituent parts of a call narrative. I had them read the calls of Abraham, Moses, Isaiah, and also the baptism of Jesus. They listed all of the elements of a call narrative for each, discussing ways in which the pattern is evident in each and ways in which certain elements might be absent. Students narrated each passage and each passage had ample discussion. By the end, they knew rather well how to identify a call narrative, what the constituent parts of a call narrative are and even why they matter. They knew all of this not because I told them so, but because they had engaged the text for themselves. They now had assimilated knowledge and learned how to interpret biblical text in a sophisticated and nuanced way.

A second way in which I apply the method is as a means of assessment. For each term, I assign about five written narrations. These are minimal assignments, consisting of 500 words in which the student must read a text and re-tell the contents of the text in their own words. You might be surprised at the effectiveness of this tool. I find that students learn to really pay close attention to what they are reading. They are usually able to get on paper a good amount of details from the text and in the sequence that the text presents them. I am also able to see places where students are not understanding the text or have lost focus on the text. I also use the written narrations as a means to provide feedback on writing mechanics. College students who have never written in the biblical studies discipline still need to attend to proper grammar, spelling, punctuation, sentence structure, verb tenses and organization of paragraphs. It is only after doing several written narrations that I pass them on to doing more substantial written projects involving thesis statements and argumentation.

One of the challenges that written narrations presents to students is to capture the essence of a reading in three categories: details, sequence and vocabulary. I give them feedback on each. I might ask students to re-tell in their own words the story of the exodus. They cannot merely copy the text of the Bible. They must begin selecting elements to write. While selecting, they must arrange them properly. These types of skills are necessary in higher forms of writing where they will be researching many texts (both primary and secondary sources).

Students Who Can Think

Ultimately, the goal of my application of this method is to cultivate students who can think. I found myself more and more frustrated at test scores and student aptitude when using the more traditional method of lecturing. With this method, created by Charlotte Mason, I find that students are scoring as well or better on tests and they are growing in their ability to discuss in mature and sophisticated ways the subject matter surrounding biblical studies.

The minds of students that are brought into contact with texts of high quality are raised to new heights. Their minds are challenged and exercised in ways that create a hunger and thirst for extended mental activity. I still run into the problem of students who want to merely pass the next exam. But I think despite this sentiment, they are also eagerly cultivating practices that will feed their curiosity and maintain an active thought life after they leave my classroom.

From my vantage point as a member of a biblical studies faculty, this afterlife of thought is imperative. The reason for this is that the primary location in which biblical studies resides is outside the academic domain. It is in religious and cultural discourse that most people engage with the Bible and its attendant literature. Only a small number of our students will ever go on to engage with biblical studies as academicians. But students who are trained to think rather than merely acquire (and quickly forget) a set of facts about the Bible will be properly equipped to partake in the wider discourse surrounding the Bible in our culture.

Leave a Reply