We have come full circle in this series on Aristotle’s intellectual virtue of prudence or practical wisdom. Prudence is one of those forgotten gems of the classical educational tradition. Its proper flowering is the result of early instruction, long reflection and the blooming of rationality in man. Discipline, early training in habits, examples and good instruction about the real differences between things—all play a role in the acquisition of prudence. But prudence itself comes through a pedagogy of dialectic, rhetoric, and ethics, since it is concerned primarily with a person’s ability to deliberate correctly and act with regard to human goods. Moreover, practical wisdom has its leadership varieties in management and politics that we can provide opportunities for students to develop in our schools.

We must aim at graduating practically wise young men and women, if we are to restore the moral, intellectual and spiritual virtues as the proper ends or goals of education. Instead of limiting education to Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive domain objectives, we should embrace a baptized prudence.

Aristotle’s prudence has its limits, however, as well as its transcendence. Like artistry, prudence itself is not enough for the Christian educator, but it can participate in or integrate with the other goals of education. In this article we will attempt to map out those limits of prudence and also address the possibilities of prudence for transcending into higher realities. To continue our metaphor of the head, heart and hands from earlier in this series, we have noted that the artistry of the hands is not enough, but we must enter into the deeper realms of the heart (i.e. prudence); in a similar fashion, the heart itself will, on its own, come up short. After all, “the heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick,” according to Jeremiah (17:6 ESV).

The Limits of Perfect Prudence and Self-Interest

This Christian view of the heart’s deceitfulness is not simply a commentary on how hard it is for a person to develop genuine prudence, the equivalent of an Aristotelian claim for its rarity, “A man of practical wisdom, who can find?” Instead, it speaks to the thoroughgoing corruption of human prudence itself. Let me explain what I mean. Given Aristotle’s analysis, prudence consists of fear and hope undergirded by natural self-love. Definitionally prudence aims at my own personal human happiness. Since that requires good friends in a polis or city-state involving specialization to provide the good things of life, as well as the public justice of reciprocity and law-abiding citizens, then my own interest coincides with the manifestation of the moral virtues.

However, Aristotle does not sufficiently address the question posed by the biblical book of Job, why good conduct should remain prudent if it no longer leads to personal eudaimonia. The Satanic claim in the book of Job is that a prudent form of righteousness devolves ultimately into mere self-interest, and when tested it amounts to no more than punishable wickedness. In fact, dependent as it is on an accurate assessment of the particular realities of human life, Aristotelian prudence operates within an immanent frame of reference, rather than a transcendent one, to use the terms of Charles Taylor (see A Secular Age).

While Aristotle maintains an under-the-sun perspective on the correspondence between righteousness and earthly reward, the book of Job unveils a transcendent perspective held roughly in common with Plato, Aristotle’s predecessor, who likely struggled with the injustice of Socrates’ execution in a way that Aristotle did not. While the issue addressed by Plato’s Republic was first and foremost justice rather than practical wisdom, the character of Socrates at least took up the extreme objection of the ring of Gyges. Injustice becomes more prudent than justice if a man has the capability of getting away with it, pictured well by a ring of invisibility. Absolute power, and with it absolute prudence, corrupts absolutely. And on the other hand, when given the appearance of injustice, “the just man will have to endure the lash, the rack, chains, [362a] the branding-iron in his eyes, and finally, after every extremity of suffering, he will be crucified, and so will learn his lesson that not to be but to seem just is what we ought to desire” (361e-362a).

Christians have seen in this passage of Plato a proto-evangelion to the Greeks; in addition to the verbal and situational similarity to the passion of the Christ, even more impressive might be its intended effect: to chasten the limits of a worldly Greek wisdom. As the apostle to the Gentiles would put it about four centuries later, “So then Jews ask for signs and Greeks seek wisdom, but we preach a crucified Messiah, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to gentiles” (1 Cor 1:22-23, orig. trans.). Why is such a proclamation foolish? Because who would follow a leader so lacking in practical and political wisdom, that he would end up a public failure, executed as a lowly criminal! Plato’s mysterious and extended discourse in the Republic is intended to provide a mystical as well as rational answer to the dilemma of righteousness and self-interest. The answer ultimately becomes dependent on mythical tales of the afterlife and revelatory accounts of the soul like the myth of Er. In this way, Plato’s wisdom embraces a transcendence similar to Christianity but which is lacking in Aristotle.

Aristotle’s definitional argument against this involves the claim that it is mere cleverness, and not practical wisdom which can manipulate ends in a morally neutral or corrupt manner. Prudence itself caps all the virtues and makes them true or genuine: “Therefore, as in the part of us which forms opinions there are two types, cleverness and practical wisdom, so too in the moral part there are two types, natural virtue and virtue in the strict sense, and of these the latter involves practical wisdom” (VI.13). Not even natural virtues, or mere propensities towards the right way of living or doing something qualify, but only the wholeness of the moral excellences governed by reasoned practical wisdom: “It is clear, then, from what has been said, that it is not possible to be good in the strict sense without practical wisdom, nor practically wise without moral virtue.”

In one sense, we could rightly criticize Aristotle for cooking the books here. If the definition of the correct mark for any of the moral virtues amounts to what the prudent man would choose, how do we actually know the difference between cleverness and practical wisdom, since the clever man might suppose himself to be practicing all the virtues? And we, lacking in full prudence, have little basis on which to judge the clever man for his Machiavellian prudence and political artistry. Aristotle does not give us hope of a transcendent frame of reference from which to call into question the machinations of our prudential self-interest. We have entered a circularity of reasoning; he may in fact describe the truth of the matter, but that does not enable a corrupt human person to actually enter into the loop of perfect virtue, governed by practical wisdom.

The Limitations of Human Calculation and Control

Aristotle would likely object to this challenge by stating that we are looking for the wrong sort of precision in his ethics, when we aim at a circular perfection of virtues (see Nic. Ethics I.3). The point is to give us enough of a sense to be getting on with as we take aim at various human goods. Life isn’t perfect, choices are complex, and chance or luck must be given its due in human affairs. In this way, Aristotle would prefer to emphasize a different limit of prudence, not the dilemma of self-interest, but the limitations of human calculation and control in a complex universe.

According to Herodotus, the wise man Solon famously questioned King Croessus’ claim on happiness, given that the gods are temperamental and a man’s fortune’s can quickly turn from better to worse or vice versa. In book I ch. 10 of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle acknowledges the role of chance in contributing to happiness. While he ultimately disagrees with the conclusion of Solon, that we should only pronounce happiness upon an individual when we’ve seen the end of their life, nevertheless he acknowledges the limits of control available to the prudent individual:

Now many events happen by chance, and events different in importance; small pieces of good fortune or of its opposite clearly do not weigh down the scales of life one way or the other, but a multitude of great events if they turn out well will make life more blessed (for not only are they themselves such as to add beauty to life, but the way a man deals with them may be noble and good), while if they turn out ill they crush and maim blessedness; for they both bring pain with them and hinder many activities. Yet even in these nobility shines through, when a man bears with resignation many great misfortunes, not through insensibility to pain but through nobility and greatness of soul. (Rev. Oxford Trans., 1739)

Aristotle’s ultimate conclusion is still that moral and intellectual excellences, as activities, have a staying power in human life that mostly overcomes the changes and chances of fortune. Excellent activities “are more durable because those who are blessed spend their life most readily and most continuously in these,” and therefore the happy man “will be happy throughout his life,” for “he will bear the chances of life most nobly and altogether decorously” (1739).

We can note that Aristotle’s philosophy does leave room for the fact that even the most perfect prudence does not have all resources available to turn all events to its own good. In fact, we might even say that there is nothing to prevent prudence itself from leading to catastrophic failure. You could make the absolute best decisions with the knowledge available to you and still be undone by circumstances. Aristotle had a proper appreciation for the nature of tragedy; sometimes in this world the great-souled individual can meet with extreme hardship. In such cases, we would do better to appreciate the limits of practical wisdom to bring about human blessings, rather than throw up our hands at the value of prudence at all. In a way, Aristotle anticipates a Stoic “resignation” in the passage quoted above. Epictetus famously taught his disciples that, when kissing their child goodnight, they should call to mind the fact that the one they love is mortal and could die tomorrow. Far from the coldness that Stoics are criticized for, such reflections as “memento mori” (“Remember that you will die”) should increase gratitude and an emotional tenderness, alongside the nobility and decorousness that Aristotle has named.

Christian Suffering and Purified Prudence

Christians, likewise, endorse a submission to providence that chastens and humbles those proud of their own prudential reasoning. Job’s response to his third grand misfortune stands as a model for Christian suffering: “Then Job arose and tore his robe and shaved his head and fell on the ground and worshiped. And he said, ‘Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return. The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord’” (Job 1:20-21 ESV). The audience understands from the transcendent visions of the heavenly court that Job’s suffering comes because of a cosmic test posed by the adversary, but Job himself is left none the wiser for why his wise and righteous life has fallen short of its natural reward. Nevertheless, his worshipful submission to a hard providence is genuine and complete, even if he ends up answering the accusations of his “friends” by challenging the justice of God. Job is never given an answer, and so the implicit conclusion of the book is that the faithful must embrace righteous suffering regardless of prudential reward.

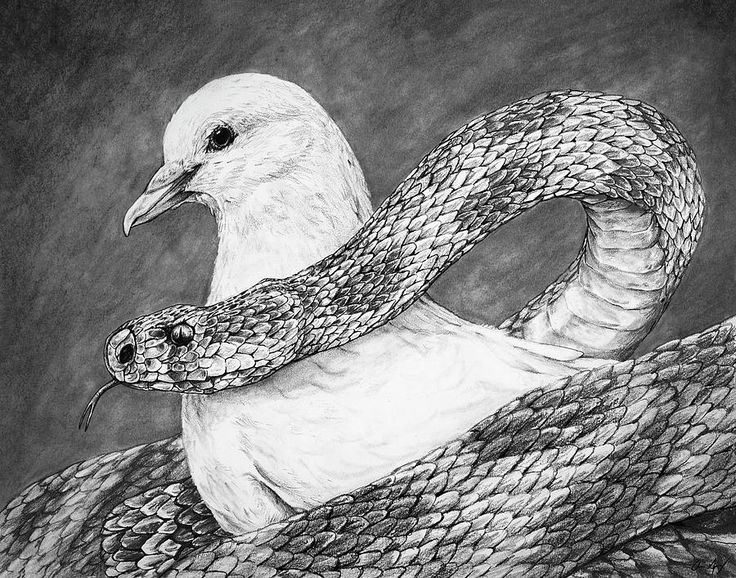

We have already had occasion to reference Jesus’ endorsement of a baptized prudence, “Be wise [phronemoi] as serpents but innocent as doves” (Matt 10:16b). But the context is instructive for the current topic. Christian prudence must uniquely transcend self-interest in a world that is in violent opposition to the gospel. The chapter begins with the twelve apostles’ particular mission to cast out demons, heal the sick and proclaim the kingdom of God, but the nature of Jesus’ instructions in the chapter seems intended to characterize the Christian mission throughout the church age. Jesus endorses a unique sort of anti-prudence in terms of the disciples’ preparation for the journey: “Acquire no gold or silver or copper for your belts, no bag for your journey, or two tunics or sandals or a staff, for the laborer deserves his food” (Matt 10:9-10).

The disciples are sent out “as sheep in the midst of wolves” (10:16a), innocent victims intentionally led forth to be falsely accused, flogged, dragged before authorities, hated by all and delivered over to death. Jesus is going to put the dilemma of Plato’s Republic and Job on display on a grand scale with the Christian apostles and martyrs. As the apostle Paul explains, “For I think that God has exhibited us apostles as men sentenced to death, for we have become a spectacle to the cosmos, both to angels and men” (1 Cor 4:9). Christian prudence is transformed by faith and hope to be “sorrowful yet always rejoicing” (2 Cor 6:10). Christian students become like the teacher Jesus, who is hated and persecuted by the world (Matt 10:24-25). In so doing they deliberately choose to accept less than earthly happiness for the sake of transcendent happiness. They are commanded, “Deliberate about [phroneite] the things above, not earthly things. For you have died and your life is hidden with Christ in God” (Col 3:2; orig. trans.). They fear the God who controls eternal destinies over human authorities and worldly rewards (see Matt 10:26-33). This wisdom is the substance of faith itself, which sees the unseen, and it effects a remarkable transformation on the nature of prudence.

Christian prudence is, at the end of the day, so remarkable that it hardly looks like prudence at all, when gazed on from this angle. And yet there is a sort of rational calculation to it. The introduction of eternal judgment, and therefore the heightened stakes of an eternal weight of glory or misery, radically upends the rational calculation of human goods. This enlightened prudence dictates not only the outcome of Pascal’s wager (Belief in God is the only rationally self-interested course of action, given the possibilities of heaven and hell.), but also a life of radical self-sacrifice. The pearl of great price of eternal happiness claims from us any cost, any sacrifice in earthly goods. As Jim Elliott, the martyred Christian missionary to Quechua Indians of Ecuador, famously wrote in his journal on Oct 28, 1949: “He is no fool who gives what he cannot keep to gain that which he cannot lose.”

Christianity thus resolved the corruption of self-interested prudence through the call to take up our individual cross and follow Christ, through personal suffering to infinite joy beyond. In this context the golden rule to do unto others as we would have them do unto us can actually find fulfillment, because a dove-like hope has quieted the serpent of self-interest. Prudence is transcended but it remains even while swallowed up in faith, hope, and love. After all, the “unblushing promises of reward” in the New Testament (to quote Lewis’ “Weight of Glory”) prevent us from claiming unselfishness as a virtue in itself. The fear and hope inbred through natural self-love are not abandoned but grow up into full manhood, as it were. Christians do not throw out prudence entirely, but embrace a baptized and purified prudence of faith, hope and love.

“The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” (Prov 9:10), but in the transformation of wisdom into perfect love, fear becomes faith and only prudential love remains (see 1 John 4:17-18). As St. Paul concludes,

Love never ends. As for prophecies, they will pass away; as for tongues, they will cease; as for knowledge, it will pass away. For we know in part and we prophesy in part, but when the perfect comes, the partial will pass away. When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I gave up childish ways. For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I have been fully known. (1 Cor. 13:8-12)

The Christian, then, cannot agree with Aristotle that the philosophic wisdom or sophia characterized by knowledge and comprehension is the highest intellectual virtue. For him, the Unmoved Mover sits in pure deistic contemplation and therefore non-acting philosophic wisdom is crowned king of the intellectual virtues. The Christian worships a God whose steadfast love endures forever, who in His very being is love, who is Eternal Act. And so, not only is our partial knowledge dwarfed by his perfect perception of all things, knowledge itself passes away in prudential love, as we come face to face with the living, acting God.

Prudence and the Other Intellectual Virtues

Of course, such theological reflections do not negate the way in which intuition, scientific knowledge and philosophic wisdom properly transcend practical wisdom. We are simply acknowledging that the theological virtues of faith, hope and love uniquely draw up the life of prudence into themselves, and in this way lead prudence beyond and above the intellectual virtues of the head. The heart transcends the head in the realm of the spirit. But it is not less true to remark on the ways that the head stands above the heart. The classical educational endeavor itself requires this. Have I not before remarked on the joy of learning for its own sake?

The utilitarian and practical perspective on schooling and learning tends toward a reductionism that views knowledge simply as power. Prudential learning looks to advantage and endeavors to provide for earthly needs by a course of schooling that will lead to a good job with a good salary. But in the actual course of learning, new loves and affections are found. The beauty of education is that often a study begun for some advantage becomes an end in itself. There is a higher nobility found in the disinterested enjoyment of knowledge for its own sake, and, whatever our theological comments may have seemed to indicate before, this too is a form of love. The love of learning and the love of reality for itself and not merely as a means is part and parcel of full intellectual virtue. This limit and transcendence of practical wisdom occurs naturally and is not a rare mystery beyond our normal experience. Observation and calculation, with a view to the self, almost of its own accord will move a person towards a real encounter with the other as an end in itself.

Such an experience of prudence transcending into disinterested intuition, knowledge and wisdom is almost proverbial. From thinking of ourselves we become lost in contemplation of curious mysteries. The boy who has gone to collect firewood stops to look at a piece of wood and is mesmerized by the moss growing on it, then the insects crawling about, and his practical task forgotten, he freely spends precious minutes indulging his curiosity. This too is part of a full life engaged in the good things of the created order God has made. And so, we must progress still further up and further in, to account for the full beauty and flowering of human intellectuality. The life of the mind has its own rewards. To these we must turn next in our series on Aristotle’s intellectual virtues.

Leave a Reply