Classical school leaders often emphasize the centrality of mentorship in the educational process, particularly in grades 6-12. They have wisely observed that the junior high and high school years are a pivotal phase in a person’s development. As students gradually spend more time with peers in settings without their parents, small yet formative opportunities emerge for these students to make decisions for themselves. Overtime, these decisions will form nothing less than their personality and character. Thus, the presence of wise and intentional mentors who can offer advice to these students becomes all the more crucial.

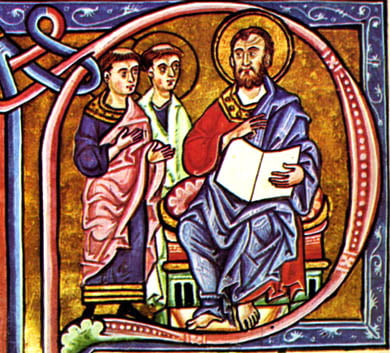

In a similar way, the young church leader Timothy benefited from the counsel of the apostle Paul. The Book of 1 Timothy is essentially a letter of mentorship that Paul writes to Timothy to support the young leader as he seeks to shepherd the Ephesian church. Contextually, pernicious false teaching had infected the community, located in a wealthy, coastal city of the Roman Empire. Paul knew that if Timothy was going to successfully lead the Ephesian Christians through such troublesome times, he was going to need guidance.

In this article, I will explore the guidance Paul provides Timothy with the aim of drawing out general principles of mentorship. By doing so, I hope to introduce a biblical approach to mentorship that moves from theory to practice in the context of local church life.

Right Doctrine

To begin, it is worth noting that Paul addresses his letter “To Timothy, my true child in the faith” (1:2). From the offset, Paul makes his relationship and love for Timothy clear. Though he will soon proceed through a list of mandates, the security of the relationship is never in question. Thus, Paul begins his mentorship letter with a key move: establishing trust.

Following the introduction, Paul transitions quickly to the root issue in the Ephesian church: false teaching. As biblical scholar Frank Thielman notes, “Letters like this were commonly sent in antiquity by a government official to a subordinate upon the subordinate’s resumption of some new public responsibility”.1 In this way, the letter serves as both a reminder of duties and as a public commission.

False teaching had plagued the church in Ephesus, spreading as such. The only way to end the plague is to remove it from the organism. In this case, Paul’s counsel for Timothy is to charge the church to teach only what is true and in full alignment with the gospel of Jesus Christ (1:11).

The key takeaway for mentorship is that ideas matter. They serve as the rutter of the ship. Mentors should be careful to not move too quickly to behaviors and practices when these are simply visible manifestations of some animating idea. In the case of the Ephesian church, the congregation was moving toward disorder as a result of the inception of heretical doctrine. Likewise, a person’s life trajectory can shift radically by the ideas they embrace and live by. Thus, the very first mentoring conversation should often focus on ideas and what the student views as her basic life principles.

Godly Conduct

Effective mentors cannot stay in the ideological realm for long, however. Following true doctrine, Paul impresses upon Timothy to promote conduct, or behavior, and godliness in the church. From worship approaches to style of dress, Christians are to live peaceful and quiet lives, “godly and dignified in every way” (2:2).

This godly approach to living must first and foremost be modeled by bishops and deacons. Notice that Paul does not leave it to Timothy’s imagination to determine the specifics of the godly conduct Paul envisions. Rather, he specifically elaborates on key character traits, familial relationships, and self-control over potential vices such as drunkenness and greed.

With these qualifications of church leaders in view, we can easily make a connection to the classical idea of virtue, that is, human excellence directed toward human flourishing. If the church in Ephesus is going to emerge from the disorder generated by false doctrine, its leaders must be freed from the slavery of the appetites, and become servants of Christ alone.

Likewise, effective mentors should discuss with their students what portrait of their future selves the Lord is calling them to become. Encourage them to be as specific as possible. What will they do for fun? What skills will they have mastered? How will they treat other people? How will they navigate complex topics like social media or peer pressure? They can then begin an honest conversation of whether their current conduct matches this desired trajectory.

The Will to Train

Right doctrine and godly conduct will establish the path for Timothy, but to go the distance, an additional step is required: the will to train. Train for what? Godliness according to the words of the faith (4:6). He compares the reward of bodily training to training for godliness in that the latter reward is experienced both in the present life and the life to come (4:8).

The idea of training appears often in our work at Educational Renaissance, particularly as it relates to the modern notions of possessing a growth mindset and engaging in deliberate practice. Research in elite performance has shown that the key to mastery in any skill or discipline is to practice with the right attitude and in the proper way.

In the Christian faith, we are to train as well, though we must be careful to train for the right objective. The Bible is clear that we do not train to earn our salvation, but to live out our salvation. Salvation is a free gift for a person to accept. It is the result of the gracious work of God, the exact opposite of any sort of result through human training. And yet, when we did receive salvation through conversion, the training regiment sets in.

The topic of training for godliness is a fascinating one to bring up in a mentoring conversation. The metaphor has a way of underscoring intensity and dedication of growing in Christlikeness in a manner that the idea of sanctification does not. By mentors taking their conversations to the deeper level of spiritual growth, they fuse together true doctrine with godly conduct in a way that will cause the student to truly think differently about how to steward their lives most wisely.

Conclusion

This exploration of 1 Timothy regarding principles of mentorship is merely an introduction into what is truly an expansive topic. There is much more to cover in Paul’s school of mentorship found in 1 Timothy, including such topics as devotion to scripture, exhibiting compassion, and practicing true contentment. As mentors plan out their meeting with students, these are all worthy topics to discuss. Following Paul, mentors taking a multi-dimensional approach will help students grow in not just one area of their lives, but holistically, instead, in a way that allows these dimensions to complement one another.

- Thielman, Frank. Theology of the New Testament (Zondervan, 2005). 413.

Leave a Reply