Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Is it possible that imitation is also the pathway to learning? In the late 1990s and early 2000s, scientists at the University of Parma published a series of studies singling out neurons that respond both when accomplishing a certain action and also when observing others accomplishing a certain action. We might call this colloquially the “monkey see, monkey do” paradigm, perhaps all the more appropriate as the initial studies were done on monkeys.

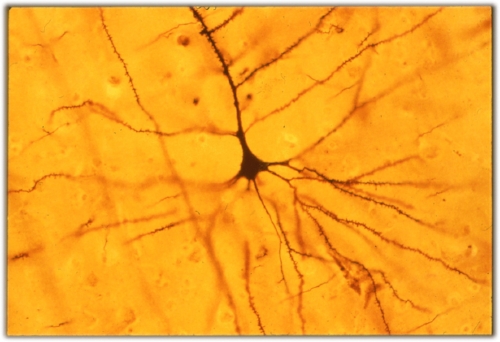

In 2010, a study took mirror neurons to the next level by identifying mirror neurons in humans. Scientists were able to utilize the intracranial electrodes implanted in 21 patients who were being treated for epilepsy. These subjects were presented with a number of facial expressions and hand-grasping movements to determine cellular activity in the brain. They recorded “extracellular activity from 1177 cells in human medial frontal and temporal cortices while patients executed or observed hand grasping actions and facial emotional expressions.” (Mukamel, Roy, et al. “Single-neuron responses in humans during execution and observation of actions.” Curr. Biol. vol. 20,8 (2010): 750-6.) What this means is that humans at the neurological level respond to the actions of others. There’s a link between observed action and performing the same action. The implications of mirror neurons for bolstering our understanding of the process of learning are immense. In this article we will explore some of the ways we can increase our awareness of neuronal activity in our students as well as practical strategies to optimize learning.

Do Mirror Neurons Even Exist?

Almost immediately after the groundbreaking study of mirror neurons in human studies, the idea of mirror neurons captured the collective imagination of society. Ramachandran’s popular TED talk boldly claimed that mirror neurons “shaped civilization.” It was all too easy to jump from neurological phenomena to claims of mind reading and an easy pathway to improving a free throw simply by watching expert videos. These claims seemed too good to be true, and in large part they are too good to be true.

Thus, when Gregory Hickok came out with his book, The Myth of Mirror Neurons (Norton, 2014), much of the momentum that had built up around mirror neurons was halted. In a nutshell, Hickok began to question the claims being made regarding mirror neurons. As a language specialist, he simply didn’t see the empirical evidence in his field of specialization nor in other fields, particularly as it relates to “action understanding.” His work points out “the many ways that the theory falls short on logical or empirical grounds.”

From the skepticism of Hickok and others, a taming of the field took place where more modest models were proposed. The current debate questions whether the mirror effect is based specifically in a mirror neuron, or whether there is a mirror system that combines multiple systems such as the visual cortex and premotor cortices (see e.g., Cecelia Hayes, et al “What Happened to Mirror Neurons?” Perspectives on Psychological Science,vol. 17,1 (2021): 153-68.) It is clear that areas of the brain “light up” when an individual sees the actions of another individual. Now the question is what mechanisms are activated when this occurs, and (more important for our purposes) what can we learn about human learning from these areas of the brain. Whether mirror neurons actually exist, it does seem that there is a mirroring system in place which gives us some potential to utilize imitation based on visual and motor inputs.

Visual and Motor Connections

Even though debate remains as to what mirror neurons are and how they operate within the brain, there are some fascinating connections that are almost intuitive. To mirror another person, one must be able to see them and then do actions in a similar way. Thus the visual cortex and motor neurons are central to what is going on with this mirror effect. Let’s break this down a bit further.

Both learning and memory are closely associated with visual inputs. Not only do we need visual inputs to read text, converting symbols into units of meaning, we also need visual inputs to read faces for non-verbal cues or to “read the room” for social cues. In the book Uncommon Sense Teaching, the authors describe the connection between vision and the brain:

“Your vision and hearing are processed in the back of your brain. This behind-most area matures first, in early childhood. Mental maturation—which means pruning and loss of flexibility—gradually moves toward the front of the brain. The very last area to mature is the prefrontal cortex, where planning and judgment take place. . . .The ability to adjust the brain’s connections doesn’t stop at maturity, however. New synaptic connections as well as pruning continue throughout people’s lifetimes.”

Barbara Oakley, et al, Uncommon Sense Teaching (New York: Tarcher Perigree, 2021), 90-91.

Vision is a fundamental process of the brain that comes online early in our development. What this means is that from the earliest ages we are taking in vast amounts of information through what we see and hear. One of the consequences of the mirror system is that we become what we see, in a manner of speaking. It is important, therefore, to carefully curate the visual environment of children. Presenting children with great works of art and the natural world around us stimulates a host of neural connections that cannot be duplicated with digital screens.

Movement is equally important to learning. Consider the act of writing. There are numerous fine motor skills that transform the electrical impulses of the neurons in our brains into a series of symbols that emerge almost effortlessly on the page. Aleksandr Luria writes in his book The Working Brain:

“Writing in the initial stages takes place through a chain of isolated motor impulses, each of which is responsible for the performance of only one element of the graphic structure; with practice, this structure of the process is radically altered and writing is converted into a single ‘kinetic melody,’ no longer requiring the memorization of the visual form of each isolated letter or individual motor impulses for making every stroke.’

Aleksandr Luria, The Working Brain (New York: Penguin, 1973), 32.

Learning to write involved imitation of a pattern of letters, and then eventually a pattern of phonemes in order to spell words correctly. The intersection of visual and motor cortices seems to be this mirror system where a strong exemplar is presented to brain such that it takes in these patterns in order to reproduce them with a high level of specificity.

We see these visual and motor connections not only with reading and writing, but also with a whole host of activities, from sketching to shooting a basketball. Increasing our awareness of this connection for learning should guide our decision making as we map out our classroom décor, as we schedule our days, and as we plan our lessons.

Imitation and Mimesis: The Classical Paradigm

We are mimetic by nature, at least that is what Aristotle conjectures in his Poetics. One of the exciting avenues the discovery of mirror neurons took us down is actually one that is rather quite old. The Greek term mimesis (μίμησις) means something like imitation or simulation. Both Plato and Aristotle agree that we as human beings represent nature through imitation. This occurs through poetry, literature, painting, drama, song, etc. Plato took a somewhat negative view of our mimetic nature, contemplating that the artist can never attain a full representation of the truth. Aristotle, however, took a more positive view of the imitative process, with the artist or poet creating a representation of reality that causes the viewer to experience a type of empathy with reality. In other words, the artist’s ability to bring out some aspect of truth touches us at a deep level, making us all the more aware of something profound, or tragic, or sublime, or transcendent.

The Circe Institute website provides an excellent overview of mimetic teaching. They explain mimesis with a beautiful description:

“Mimesis is an imitation, not of the outward form, but of the inner idea—not ultimately of an action, but of the idea expressed in that action. Every art and skill is mastered through these stages, whether in school or out. It is a modified inductive form of instruction in which students are led to understand ideas by contemplating models or types of them. These models can be found in literature, history, mathematics, the fine arts, music, other human arts and activities, and nature.”

“What is Mimetic Teaching?: A Lost Tools of Writing Excerpt,” (circeinstitute.org)

The web page goes on to delineate the seven stages of a mimetic lesson. At the heart of this model is imitation. The learner is presented with something and then is called upon to imitate.

Another classic expression of imitation is carried out through apprenticeship. Here the learner copies the master on their own journey toward mastery. The heart of the apprenticeship approach to learning is deliberate practice. The student is coached to acquire and hone skills across the disciplines.

The classical paradigm of imitation and mimesis have long been instrumental for learning knowledge and skills. Now recent research are identifying that there is a neurological underpinning to these time-tested modes of learning through imitation.

Paint, Sing, Act, Dance and Play

There are many practical steps we can take as educators in light of the emerging neuroscience in addition to the classical modes of mimesis and apprenticeship. Here I will spell out a few, trusting that others will emerge in your own creative planning for your students.

First, we should present to our students excellent visual content. Here we can consider great works of art. The masters we would want to imitate ought to be ever-present in our environment. But we can go beyond great works of art. Students should see examples of beautiful handwriting. They should see excellent mathematical and geometric models. They should observe the natural world, whether that is on a nature walk or bringing quality specimens into the classroom. Once we understand how important this idea of imitation is, then we can begin to bring before our students high quality examples in all parts of life.

I am quick to add here that narration dances about the connection between the visual and motor. When the student is reading or listening, the student should be visualizing in their mind by way of their imagination what is being read or told. Then in the act of telling back, that internal visualization is converted into something verbal. We are big proponents of narration here at Educational Renaissance, and there is ample reason at a neurological level to make this a regular practice in your classroom.

Second, the point of this mirror system is that our students put into practice the exemplary models placed before them. There is a moral and spiritual aspect to this. The call for excellent books is not merely to have expansive vocabulary and eloquent style. We are looking for moral virtue in the characters of literature and history. When the mind’s eye is filled with the heroic individual, we can then be called to follow that example. Consider the biblical passage of 1 Peter 2:21, “For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, so that you might follow in his steps.” At the same time that Peter identifies Christ’s suffering as the means of our salvation, he also points to Christ as the mode of living we ought to carry out, with both moral and spiritual implications.

Third, the connection between the visual and motor cortices means we need to act out what it is we are learning. I think this happens naturally when young boys and girls act out the parts of an ancient Roman battle when they are playing during recess. At a neurological level, that kind of play is linking up all kinds of synapses in the brain. At another level, children are practicing something noble. It is a way of responding to what they have visualized in their minds eye and now carry out in bodily play. There is something to becoming more and more skilled at such activities as painting, singing, acting, dancing and playing. Consider the student who has many years of practice using the drybrush watercolor technique. That student’s ability to make visual and motor connections is enhanced by that growth in skill.

New from Educational Renaissance Publishing:

Leave a Reply