How does a person become wise? What are the proper ingredients in an educational paradigm aimed at prudence? Where would we even begin? So much of K-12 education seems to have nothing to do with practical wisdom, as Aristotle defines it. How do we recover the classical goals of wisdom and virtue in earnest, and not simply as a marketing claim?

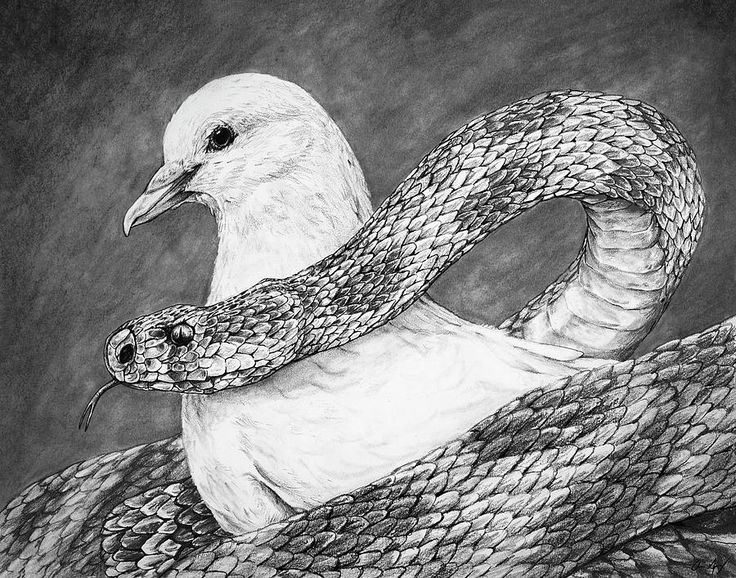

So far in this series we have had occasion to develop the Christian underpinnings for prudence. “Be wise [phronemoi, prudent] as serpents and innocent as doves” (Matt 10:16), Jesus tells his disciples, utilizing the same word for prudence that Aristotle had named among his five intellectual virtues hundreds of years before. And while the New Testament does not consistently endorse this linguistic distinction between practical and philosophic wisdom (phronesis vs sophia), still the emphasis of the Bible lands squarely on the practical ability to discern the difference between good and evil, to see through the deceitfulness of sin and value goods rightly. Augustine’s ordo amoris, or the proper ordering of loves, provides an important theological development of the Greek philosophical vision of the prudent man.

Practical wisdom is thus necessarily contrasted with philosophic wisdom (sophia), which for Aristotle involved perception (nous) of first principles and scientific knowledge (episteme) about invariable things, things that never change. We might call these invariable things eternal truths and think more readily of mathematics and metaphysics, than history and literature. What is best for human beings differs with different particulars. Christians might likewise contrast abstract or theoretical knowledge about the divine being, that He is eternal, immortal, impassible, etc., with knowing God himself in a saving relationship. As James writes in his letter, “You believe that God is one; you do well. Even the demons believe–and shudder!” (James 2:19 ESV). In the same way, prudence has the heart of action in a way that other intellectual virtues do not.

Adopting a prudential perspective thus has the potential to transform our classical Christian educational paradigm by pumping the lifeblood of practicality back into it. To do that we must now begin to answer in earnest the question of how. What are the proper methods of instructing the conscience and instilling moral wisdom? We must begin with the preliminary stages of instilling prudence in the young, before delineating a pedagogy of prudence for our older students. The full dawning of prudence requires the later stages of reflection and rationality that await higher intellectual development in high school and college years.

Can We Even Teach Prudence?

At first, in consulting Aristotle we might be tempted to despair of a pedagogy for prudence. After all, the main requirement for developing prudence in Aristotle seems to be experience, a notion that is illustrated by the fact that scientific knowledge (episteme), while technically of a higher rank among the intellectual virtues, is attainable much earlier than prudence (phronesis):

What has been said is confirmed by the fact that while young men become geometricians and mathematicians and wise in matters like these, it is thought that a young man of practical wisdom cannot be found. The cause is that such wisdom is concerned not only with universals but with particulars, which become familiar from experience, but a young man has no experience, for it is length of time that gives experience; indeed one might ask this question too, why a boy may become a mathematician, but not a wise man or a natural scientist. Is it because the objects of mathematics exist by abstraction, while the first principles of these other subjects come from experience, and because young men have no conviction about the latter but merely use the proper language, while the essence of mathematical objects is plain enough to them? (Nicomachean Ethics VI.8, p. 1803 in The Complete Works of Aristotle, vol. 2)

In modern teaching circles we are inclined to believe that it is abstractions and universals that stymie the young mind. Aristotle provides a good counter to our inclinations here, as does the documented Flynn effect: “the increase in correct IQ test answers with each new generation in the twentieth century.” In his book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, David Epstein explains the increasing understanding of abstractions for children in the modern world:

A child today who scores average on similarities would be in the 94th percentile of her grandparents’ generation. When a group of Estonian researchers used national test scores to compare word understandings of schoolkids in the 1930s to those in 2006, they saw that improvement came very specifically on the most abstract words. The more abstract the word, the bigger the improvement. The kids barely bested their grandparents on words for directly observable objects or phenomena (“hen,” “eating,” “illness”), but they improved massively on imperceptible concepts (“law,” “pledge,” “citizen”). (39)

It turns out that abstractions are not as impenetrable to the young as we had thought. The linguistic environment of modern societies, which is rich in such abstractions (if deficient in other ways…), has provided for a steady advance in this sort of thinking.

It has not, we can assert anecdotally, seemed to afford any meaningful advance in the particulars of prudence. Experience, we are tempted to believe, may not be the best teacher, but perhaps it is the only teacher of practical wisdom. We might forgive Gary Hartenburg, the author of Aristotle: Education for Virtue and Leisure (from the Giants in the History of Education series from Classical Academic Press), for claiming that the development of prudence must wait for after the conclusion of formal education (53-54).

I think that this pessimistic conclusion, however, is incorrect. Even if we must go beyond Aristotle’s admittedly incomplete writings on education (the section of his Politics which concerns education is corrupt and ends abruptly before its actual conclusion), we have reason to hope that we can influence the development of prudence in the young. In addition to a host of classical and Christian resources that answer the question, “Can virtue be taught?”, in the affirmative, as David Hicks memorably put it in Norms and Nobility (Buy through the EdRen Bookstore!), we need look no further than the great Christian educational reformer John Amos Comenius.

Sowing the Seeds of All the Virtues

You might recall that John Amos Comenius, the brilliant Czech educational celebrity of the late Reformation era, came to our aid earlier in this series on Aristotle’s intellectual virtues. His reflections helped to establish the ultimate goal of Christian education as the cultivation of all the moral, intellectual and spiritual virtues. In this way we were able to effectively replace Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives in the cognitive domain with a more holistic Christian paradigm focused on the virtues. Prudence uniquely ties together the moral and spiritual virtues at the rational center of human thought. It has therefore rightly been regarded as a hinge virtue, one of the cardinal (from the Latin cardo for hinge) virtues of classical and medieval tradition.

Comenius, also, provided us a pedagogy of artistry through his method of the arts, laid out first in his Great Didactic, then refined and developed in the Analytical Didactic, which he published much later in life. The first of these developed analogies from nature to detail a thrilling and vibrant (if at times startling) educational vision. The second delighted in the bracing air of analytical logic and method, rather than continuing the playful analogies of his first great educational work.

In a chapter of The Great Didactic entitled, “The Method of Morals” he begins by stating programmatically, “All the virtues, without exception, should be implanted in the young. For in morality nothing can be admitted without leaving a gap.” We can pause to note the natural metaphor of implanting, sowing the seeds of virtue we might say. (I explored this idea for the benefit of parents on Coram Deo Academy’s website: intro, memory, habits, ideas.) For Comenius, like Aristotle, the virtues do not “exist in separation from each other…, for with the presence of the one quality, practical wisdom, will be given all the excellences” (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, VI.13, Rev. Oxford Trans., 1808).

Comenius goes on, drawing from medieval and classical tradition, to endorse the cardinal virtues explicitly, as the hinges on which the door of virtue is swung open:

Those virtues which are called cardinal should be first instilled; these are prudence, temperance, fortitude, and justice. In this way we may ensure that the structure shall not be built up without a foundation, and that the various parts shall form a harmonious whole. (211-212)

Comenius’ ordering of these virtues seems deliberate, as he continues through them in the order named, delineating certain “fundamental rules” for “shaping the morals” and “instilling true virtue and piety” in schools (211). It is refreshing to see Comenius’ clear endorsement of the classical tradition’s call to teach virtue and establish a bedrock of piety in our students (on which we might reference Kevin Clark and Ravi Jain’s chapter on piety in The Liberal Arts Tradition).

But why does Comenius list prudence first? Most of the time the cardinal virtues are enumerated with prudence last as the crowning achievement after the preliminary moral virtues. Surely our awareness of Aristotle’s categorization of prudence as an intellectual virtue would cause us to place it after the moral virtues of temperance, justice and fortitude. We must read on to see that Comenius’s practical advice on how to instill these virtues requires the seeds of prudence to be sowed alongside every virtue. We cannot really train in virtuous habits, unless we are at the same time laying the foundation of prudence in the hearts and minds of the young.

The Method of Instruction in Prudence

Charlotte Mason distinguished her method of habit training from mere behaviorism by her insistence on going back further than simply “sowing a habit” to “reap a character”. We must sow the idea that makes the habit valuable and good. In the same way, Comenius regards prudential instruction as the basis for the development of the moral virtues. He begins by stating, “Prudence must be acquired by receiving good instruction, and by learning the real differences that exist between things, and the relative value of those things.” Surprisingly, perhaps to our postmodern ears, Comenius asserts that “good instruction” on values is not only possible, but is grounded in objective reality.

In our contemporary culture ‘fact’ and ‘opinion’ are sharply distinguished, and opinions and value judgments are classed as unimportant because they are contested in the public square. But practical wisdom is precisely concerned with, in Aristotle’s words, “that part [of the soul] which forms opinions” (Nic. Ethics, VI.5, 1801), and “correctness of opinion is truth” (VI.9, 1804). Understanding the “good instruction” of a teacher on the “real differences… between things” and the “relative value of those things” is therefore a preliminary to prudence. As Aristotle explains,

Now understanding [nous] is neither the having nor the acquiring of practical wisdom; but as learning is called understanding when it means the exercise of the faculty of opinion for the purpose of judging of what some one else says about matters with which practical wisdom is concerned–and of judging soundly. (VI.10, 1805)

The key point for our purposes is that, while understanding a teacher’s “good instruction” is not prudence itself, it does exercise the faculty of opining and judging soundly. It therefore constitutes sowing the proper seeds for prudence, or laying the right foundation, to continue with Comenius’ vivid metaphors.

Comenius elaborates on this preliminary instruction in prudence quoting from John Ludovic Vives, one of the great educators of the sixteenth century:

A sound judgment on matters of fact is the true foundation of all virtue. Well does Vives say: “True wisdom consists in having a sound judgment, and in thus arriving at the truth. Thus are we prevented from following worthless things as if they were of value, or from rejecting what is of value as if it were worthless; from blaming what should be praised, and from praising what should be blamed. This is the source from which all error arises in the human mind, and there is nothing in the life of man that is more disastrous than the lack of judgment through which a false estimate of facts is made. Sound judgment,” he proceeds, “should be practiced in early youth, and will thus be developed by the time manhood is reached. A boy should seek that which is right and avoid that which is worthless, for thus the practice of judging correctly will become second nature with him.” (212)

We can pause here to note that this sort of instruction cannot be given by a man or woman without sound judgment and some measure of prudence herself. You cannot give what you do not have. In matters of prudence, John Milton Gregory’s Law of the Teacher could not be truer: a teacher must know that which he would teach. We should also fix in our minds clearly that our modern dichotomy between fact and opinion has been entirely done away with (at least in this translation…). The fact is that riches are less valuable than friendship; you can call this an opinion or judgment if you want, but it does not reduce the importance or truth of such a fact.

Proverbs provide a collected store of such judgments or estimates of the facts of a case, which can provide a preliminary to prudence for the young. Even where the reasoning of moral sayings and aphorisms is not spelled out, they are of immense value to the young in averting prudential error in valuing things rightly. As Aristotle claims, “Therefore we ought to attend to the undemonstrated sayings and opinions of experienced and older people or of people of practical wisdom not less than to demonstrations; for because experience has given them an eye they see aright” (Nic. Ethics VI.11, 1806).

It is in the realm of prudence, then, that we must question Charlotte Mason’s outlaw of opining before children:

One of our presumptuous sins in this connection is that we venture to offer opinions to children (and to older persons) instead of ideas. We believe that an opinion expresses thought and therefore embodies an idea. Even if it did so once the very act of crystallization into opinion destroys any vitality it may have had…. (Toward a Philosophy of Education, vol. 6; Wilder, 2008; 87)

If by “opinions” we are talking primarily about personal views on contemporary issues or debatable matters of history or literary criticism where solid evidence is lacking, Mason’s point is well-taken. The precious class time should not be concerned with such trivialities and the accidence of their teacher’s preferred opinions.

But if instead we are talking about matters related to living a good life and the general human condition, with what is truly valuable in life and what dead ends and roadblocks have prevented many people for making virtuous choices, then Charlotte Mason’s opinion about opinions must be soundly discarded. If a teacher’s hard-won opinions about such matters are not worth passing on to the young, the teacher should not be employed to give care to the young. In fact, we might go so far as to state that the most important quality of a teacher or tutor of the young is that he or she be a man or woman of prudence, with the ability to give instruction in the form of good opinions about life in the midst of all the studies. As John Locke openly declares in Some Thoughts Concerning Education:

The great work of a governor is to fashion the carriage and form the mind, to settle in his pupil good habits and the principles of virtue and wisdom, to give him by little and little a view of mankind, and work him into a love and imitation of what is excellent and praiseworthy, and in the prosecution of it to give him vigor, activity, and industry. The studies which he sets him upon are but as it were the exercises of his faculties and employment of his time to keep him from sauntering and idleness, to teach him application, and accustom him to take pains, and to give him some little taste of what his own industry must perfect. (70)

The studies themselves pale in comparison to the training in “good habits” and the teacher’s instruction in “the principles of virtue and wisdom.”

So, our conclusion, for the moment, is that the teacher of the young should not muzzle herself when it comes to opining on matters of wisdom and virtue. She should proactively and deliberately seek to share all the accumulated wisdom on living a good life that she has available to her, from proverbs and sayings, passages of scripture, lessons of life from history, literature, and modern examples. It is the job of a teacher of the young to thus opine. In the next article we’ll continue to explore the methods of instilling prudence in the young through not only “good instruction” but the use of examples, rules and discipline.

Leave a Reply