In a world of seemingly endless opportunities for educational innovation, it can be difficult for school leaders to know where to focus. Should they prioritize the building of a successful sports program? How about offering generous packages of financial assistance? Will the school be known for its impressive musical productions, rigorous curriculum, or exceptional classroom teachers? And how about the school’s marketplace focus– financial accessibility, academic superiority, or programmatic breadth?1

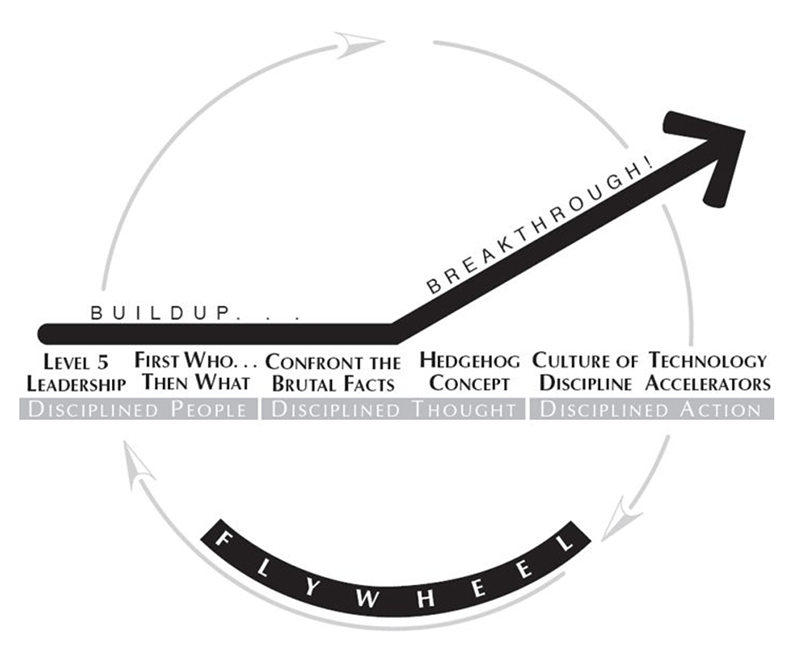

In Good to Great, author Jim Collins argues from longitudinal research that one reason organizations fail to make the jump from good to great is that they never land on their “one big thing.” He calls this “thing” the Hedgehog Concept. Collins defines it as a simple crystalline concept that flows from deep understanding about the intersection of the organization’s superior distinctive, economic engine, and abiding passion (97). Collins writes, “The essence of a Hedgehog Concept is to attain piercing clarity about how to produce the best long-term results, and then exercising relentless discipline to say, ‘No thank you,’ to opportunities that fail the hedgehog test” (Good to Great and the Social Sectors, 17).

In this blog, my final installment in a three-part series on Good to Great (you can read Part 1 here and Part 2 here), I will explore how Christian, classical schools can identify their Hedgehog Concept. Like my other two articles, it is important to remember that much of Collin’s advice is designed for businesses, not schools. Collins himself acknowledged this limitation, which led him to publish an accompanying monograph for social sectors. Nevertheless, in my own thinking, I have discovered that there are quite a few helpful instances of overlap between the business and social sector, including the need for a Hedgehog Concept. In what follows, I will unpack further the notion of a Hedgehog Concept and then offer specific guidance regarding how Christian, classical schools can find theirs.

Understanding the Hedgehog

There are three key parts to the Hedgehog Concept, all of which work together in a synergistic way. The result is a crystalline center, which becomes the core business. Once the core business is identified, the company must exercise rigorous discipline to resist opportunities that would lead it away from its center.

So what are the three parts? I will take them one at a time.

#1: What can you be the best in the world at?

This may sound like a humorous, if not arrogant, question. But it forces an organization to think deeply about what truly sets it apart in the marketplace. It is not enough to simply identify a list of core competencies. This list may get you a sly, maneuverable fox, but not a hedgehog.

Moreover, this circle is not asking what the organization wants to be the best at. Collins writes, “Every company would like to be the best at something, but few actually understand–with piercing insight and egoless clarity–what they actually have the potential to be the best at and, just as important, what they cannot be the best at” (98). In order to gain this kind of understanding, organizations need to be honest with themselves, confronting the brutal facts about what assets set them apart and what constraints might provide clarity on the direction they should focus.

It is tempting for companies who are doing well–meeting their quarterly goals and so on–to feel that they are on the path the greatness. But Collins warns that this could actually be the curse of competence. To transcend this curse, companies must resist the temptation to become complacent with brief instances of success. To achieve exceptional results over the long-term, companies should take encouragement from short-term results while continuing to strive to find their hedgehog concept, a process that took the good-to-great companies fours years on average to find.

#2: What drives your economic engine?

To identify the second circle within the hedgehog, Collins asks, “If you could pick one and only one ratio–profit per x–to systematically increase over time, what x would have the greatest and most sustainable impact on your economic engine?” (104).

For example, Walgreens made the jump from good to great when it identified its primary economic denominator as profit per customer visit. This decision led them to redesign their building design, product line, and pricing around maximizing the productivity of each customer visit. For Gillette, another good-to-great company, it would not make sense for its engine to be driven by customer visits because it does not own brick-and-mortar stores. Instead, Gillette concentrated its engine power on product per customer. Gillette focused on gaining customer loyalty through both repeated purchases (e.g. razor cartridges) and high profit purchases (e.g. non-disposable razors) (107).

For nonprofit organizations, like schools, they cannot locate their economic engine in a profit metric for obvious reasons. But nor is it sufficient to simply focus on other sources of cash flow, which Collins initially thought. What Collins learned in his research is that in the social sector, the economic engine needs to be retooled into a resource engine with three key components: time, money, and brand. The question then becomes: “How can we develop a sustainable resource engine to deliver superior performance results relative to our mission?” (Social Sector, 18).

#3: What are you deeply passionate about?

The final concentric circle in Collins’ hedgehog concept is all about passion. This is the most straightforward and intuitive of the three circles. As organizations find their hedgehog concept, their one big “thing,” it must be something that the people are excited about. Whether it is the product itself or what the company stands for, there must be an inner motivation that drives them. It is this passion that will help companies push through glass ceilings and sustain results over the long-term.

Identifying a Christian, Classical Hedgehog Concept

As we begin to explore what a Christian, classical hedgehog concept might look like, it can be helpful to shift around the order in which we tackle the circles. As a nonprofit, schools should begin with their cause–what they are passionate about and, ultimately, why they exist. When we can get clear on the mission, we can then proceed through the conceptual process.

#1: What is your school deeply passionate about?

For most Christian, classical educators, our passion falls into a few buckets. As educators, we delight in children. We love their joy, curiosity, and enthusiasm. We regularly catch glimmers of who they can become as their personal strengths and interests emerge. We are passionate about coming alongside our students to help them steward the gifts God has given them and to help them flourish as human beings.

We are also passionate about God’s redemptive work in human history. It is a stunning reality of the gospel that God has enacted a plan to reconcile fallen creation to Himself. Through the life, death, and resurrection of Christ, the kingdom of God is breaking into our world, bringing hope and redemption for all peoples of the earth who put their trust in Christ. Christian, classical education is one way we as Christians can participate in impactful work for the kingdom.

Finally, we are passionate about real and deep learning that is rooted in something bigger than, for example, workplace preparation. When we reimagine learning as the pursuit of goodness, truth, and beauty, and the formation of virtue in students, we grow excited about going on this journey ourselves and inviting students with us in this transformative process.

#2: What can your school do better than anyone else?

This is a tricky one. There are lots of ways to answer this question and different classical schools will have slightly different answers depending on their size, history, and context (see the introduction to this article for all the different potential areas of focus). However, from a philosophical and curricular standpoint, there is a unifying thread that necessarily connects truly classical schools no matter what size and location.

Here are a few examples:

- Learn in a genuine community of inquiry through discussion-based learning

- Facilitate organic student growth, free of checking the boxes of bureaucratic state standards

- Read the classics of western civilization, contemplating and digesting the riches of the tradition

- Prepare future leaders with strong character and rhetorical skills

- Equip young Christian men and women to lead lives of meaning and purpose

What about sports programs, school musicals, financial accessibility, and academic accolades? These components may be part of a particular strategic plan or initiative, but they are likely not central to the school’s hedgehog concept. For classical schools, leaders need to keep the main thing the main thing: equipping students with the knowledge, virtues, and skills they need to flourish Through a time-tested curriculum, and commitment to preserving the best of the past while gleaning insights of the present, classical schools can set apart themselves from other schools.

#3: What drives the resource engine for your school?

As you may recall, Collins believes there are three components to a nonprofit’s resource engine: time, money, and brand. The goal is to connect this resource engine to the organization’s passion and what it does best. While there is much to be said on this topic, I will comment briefly on money and brand, saving time for another day (ironically).

From a financial perspective, schools receive revenue from, generally speaking, tuition and fundraising. Therefore, schools need to exercise both business acumen and fundraising skill. They need to think carefully about how much it will cost to run the school and create a sustainable financial plan to cover these expenses. Ideally, the school will cover most, if not all, of its operational expenses with hard income (e.g. tuition and fees), freeing up fundraising efforts to fund infrastructure projects and longterm strategic goals.

On the brand component, schools can help power their resource engine by earning a reputation of achieving its mission with excellence. This reputation, which takes time to develop through consistent practices and results, will reinforce what a school can charge for tuition and how much it can raise. In this way, the resource engine works synergistically along with the other circles of the hedgehog concept. The cause of the school’s passion will mobilize donors to give. As the brand improves, emotional goodwill and mindshare will increase, growing the school’s reputation in the community. This in turn will lead to increased enrollment, more alumni, and a wider donor base. This phenomenon of momentum, which takes time over a period of sustained effort, Collins calls the Flywheel Effect.

Conclusion

In order for Christian, classical schools to faithfully serve students over the long-term, they need to identify and commit to their Hedgehog Concept. The concept begins with the emergence of a passion to equip future generations of Christians with the knowledge, skills, and virtues they need to flourish both individually and as members of society. It is then augmented with an understanding of what the school contributes to families in the communities it touches: Christ-centered, liberal arts education. Finally, the school’s Hedgehog Concept is complete when it hones in on a resource engine that connects all three circles so that they reinforce each other for longterm institutional sustainability.

- “Price, Product, Process: A Conceptual Update” in I&P, Vol. 40, No. 10. Independent School Management.

Leave a Reply