The year was 1895. Two momentous events occurred that year that would lead to a heated rivalry between Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. DuBois. The first event was the death of Frederick Douglass on February 20th of that year. He was the leading black figure of the time, speaking and writing with a level of rhetorical polish that revealed a great mind. Douglass was a towering figure in the social and political environment during the close of the 19th century. As such, his death called forth a new voice that would champion the cause of black suffrage.

The second event came later that year on September 18th. Booker T. Washington gave a speech at the Atlanta Exposition. In this speech, presented before a predominantly white audience, laid out an educational plan that would aim at the advancement of blacks in vocational or industrial trades. Washington first advised “the friends of my race” to make “friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded.” (Washington, “Address” 18 Sept. 1895) His was a message of reconciliation, spoken deep in the South, sounded the right note for those in attendance. The worry was that racial tensions would erupt in Atlanta, since Georgia had been adopting Jim Crow laws during the 1890s. It was only the following May that the Plessy v. Ferguson decision was made in the Supreme Court, upholding “separate but equal” segregation in the South.

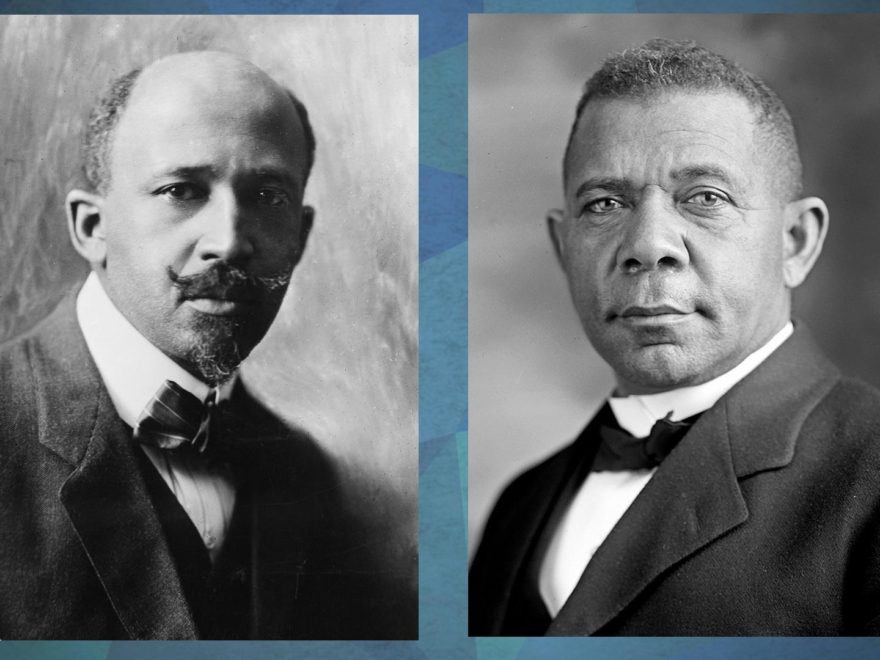

(The New York Times photo archive)

What Washington meant by “making friends in every manly way” he immediately spells out in his speech:

“Our greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour, and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life; shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful. No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top. Nor should we permit our grievances to overshadow our opportunities.”

Booker T. Washington, “Address by Booker T. Washington“

(For teachers interested in investigating primary sources, you can access the manuscript of the speech at this Georgia Historical Society webpage and listen to an audio recording Washington made in 1908 of excerpts from his speech available at this Library of Congress webpage.)

The Atlanta Compromise

For Washington, the strategy to make black lives better is to forgo such things as campaigning for government positions or contending for positions in the ivory tower of colleges and universities. It is a strategy that makes sense. Catch the wave of the booming industrial economy in the South and ride that wave to a better future. Washington’s speech became known as the “Atlanta Compromise” in part due to the cooperative program he laid out, but also because it caught the industrial wave, but also the wave of Jim Crow laws and segregationism.

Despite the rivalry that soon emerged between Washington and W. E. B. DuBois, the Atlanta speech was at first celebrated by DuBois. In a brief letter dated 24th September of 1895, DuBois writes:

“Let me heartily congratulate you upon your phenomenal success at Atlanta—it was a word fitly spoken.”

It is not altogether clear exactly what DuBois is congratulating here. Was he particularly impressed by the content of the speech or did he recognize the emergence of a new leader to take up the mantle of Douglass? DuBois was himself an emerging leader although he was over a decade younger than Washington. Perhaps the heart of DuBois’ message to Washington centers less on the content of what was spoken and more on DuBois’s recognition of the role Washington could play as the heir to Douglass. No matter how we read the praise DuBois sends to Washington, it did not take long for DuBois to reconsider his position on black education and to challenge the very message of the “Atlanta Compromise.”

A Study in Contrasts

Washington and DuBois could not have been more different, and perhaps that accounts for the difference in their perspectives on education. Booker T. Washington was born into slavery on a plantation in Virginia. He was nearly ten when the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, about which he writes that “some man who seemed to be a stranger (a United States officer, I presume) made a little speech and then read a rather long paper—the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased.” (Up from Slavery 20-21) As a freedman, Washington worked in the coals mines while attending Hampton Institute. At the age of 25, Washington was appointed as principal to what is now called Tuskegee University in Alabama. Tuskagee was a place where Washington could put into practice his “head, hearts, and hands” approach so that students were trained “to return to the plantation districts and show the people there how to put new energy and new ideas into farming as well as into the intellectual and moral and religious life of the people.” (Up from Slavery 160).

DuBois, on the other hand, was born into a free black family in Massachusetts, attending integrated schools during his childhood. He went to Fisk University where he encountered racism and segregation for the first time. After Fisk he went on to earn another bachelor’s degree from Harvard and then completed graduate work at the University of Berlin. He returned to the States and became the first black to earn a PhD from Harvard. DuBois was offered a position at Tuskagee, which would have seen him working alongside Washington, but instead took a position at Wilberforce University in Ohio. Later he taught at Atlanta University and developed a prominent voice domestically and internationally in scientific sociology. It is no surprise, then, that, as an academic tour de force himself, DuBois would champion a very different educational vision than Washington. He focused on the liberal arts with a view to raising up leaders within the black community who would be able to take up prominent positions in politics and business to enact real change in society.

The Talented Tenth

The thesis DuBois developed took on different nuances over time. In an essay entitled “The Talented Tenth,” DuBois lays out his philosophical conviction that the object of education must be the formation of the person rather than money-making or technical skill.

“Men we shall have only as we make manhood the object of the work of schools—intelligence, broad sympathy, knowledge of the world that was and is, and of the relation of men to it—this is the curriculum of that Higher Education which must underlie true life.”

W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Talented Tenth,” 33-34.

He goes on to demonstrate that through the generations leaders rose up even during slavery to provide leadership that ultimately led to emancipation. These were exceptional people, which proves his point that the training of exceptional leaders is what will continue to lead equality of the races. DuBois lays out the program of study for students at his Atlanta University.

“Here students from the grammar grades, after a three years’ high school course, take a college course of 136 weeks. One-fourth of this time is given to Latin and Greek; one-fifth, to English and modern languages; one-sixth, to history and social science; one-seventh, to natural science; one-eighth to mathematics, and one-eighth to philosophy and pedagogy.”

W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Talented Tenth,” 49.

This sounds very much like the liberal arts education we have promoted in the classical Christian educational renewal movement. From DuBois’ perspective, it is the liberal arts that will train up the next generation of black leaders who will transform society.

Not So Different

Now the delineation of these two educational programs has thus far been expressed in stark terms. Washington’s “Atlanta Compromise” emphasizes industrial training while DuBois insists on a liberal arts education for the “Talented Tenth.” It is all too easy to draw lines between these pedagogical models in hindsight. Yet there are many ways in which we may see overlap between these two. Yes, the divide between DuBois and Washington was exacerbated by the essay DuBois wrote in The Souls of Black Folk entitled “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others” in which he was critical of Washington’s autobiography Up from Slavery. However, DuBois later gave perspective to exactly what was at the heart of their disagreement. It was not the educational program, per se, but the trust that dutiful, diligent work would lead to acceptance of a black work ethic among whites in the South. He writes:

“I realized the need for what Washington was doing. Yet it seemed to me he was giving up essential ground that would be hard to win back. I don’t think Washington saw this until the last years of his life. He kept hoping. But before he died he must have known that he and his hopes had been rejected and that he had, without so intending, helped make stronger — and more fiercely defended — a separation and rejection that made a mockery of all he had hoped and dreamed.”

“W.E.B. DuBois,” The Atlantic Monthly, Nov. 1965

The hopes and dreams of Washington were dashed not because of a blind faith in his educational program, but in his faith that respectable work would be universally praised by a watching world. If we were solely to look at the educational results in the lives of the individual students, a different perspective emerges. Creating educational programs with the aim of making radical changes in society misplace the actual educational aim. Developing human beings as whole persons is a more fundamental aim, and we are probably safe in saying the programs developed by both Washington and DuBois met this aim.

Moral Formation

My claim that Washington and DuBois are not so different rests not in the details of their program of study, but in the importance both men placed in the moral formation of students. Washington’s technical education placed emphasis on the moral and religious aspects of educations.

“We wanted to give them such an education as would fit a large proportion of them to be teachers, and at the same time cause them to return to the plantation districts and show the people there how to put new energy and new ideas into farming, as well as into the intellectual and moral and religious life of the people.”

Up from Slavery 160

We get a similar hint at moral and spiritual development in The Souls of Black Folk. For instance, DuBois writes, “sometime, somewhere, men will judge men by their souls and not by their skin.” (The Souls of Black Folk 261) In his essay “The Talented Tenth,” he delineates two main objectives for education in a post-emancipation society:

“If then we start out to train an ignorant and unskilled people with a heritage of bad habits, our system of training must set before itself two great aims the one dealing with knowledge and character, the other part seeking to give the child the technical knowledge necessary for him to earn a living under the present circumstances.”

“Talented Tenth” 58

Although DuBois was critical of Washington’s compromise, we see here a recognition that educated people must make a living. Yet, the first of the two great aims is knowledge and character. On even a cursory reading of DuBois, one is struck by his thorough knowledge of the Western canon, or what we might call the traditional liberal arts. So by “knowledge” we are not talking about a mastery of facts and figures prominent in an industrial age, but of the long tradition of great authors and ideas. This is knowledge that DuBois sees as transcending racial divide, even though it has come to be thought of as a collection of dead white men’s thoughts. Indeed, DuBois sees this long tradition as the foundation for character and creating a moral society.

So, where we find overlap in the Washington-DuBois debate is on this concept of morality. And it is on this concept we should give serious consideration to the ideas both men propound. These two men were seeking a Renaissance in their time, and in many ways they were the architects of a flowering of black culture. I am quick to add that their reflections on education are instructive not only for a minority culture, but promote global considerations that are crucial for us to get right in our current educational renewal movement.

Ideas not Ideology

Washington and DuBois both seek to promote the great society; one in which racial lines are erased and mutual respect leads to intellectual, moral and technological advance. Both men sought to utilize great ideas as a means of train young men and women. Great ideas are not the domain of one class, sect, race or people. They challenge us and through that challenge transform us through what we might call the dialectical process. We weight different ideas, discerning and discriminating, in order to arrive at a synthesis. Great ideas generate new ideas, transforming not only our minds but also our characters.

Contrast this with ideology. An ideology is a system of ideals often accepted uncritically and unquestioningly. Our current political and social landscape is rife with conflicting ideologies. The impact of the conflict of ideologies is that camps – whether to the right or to the left – attempt to commandeer institutions, whether that be media, government or schools. No longer is our society marked by discourse, dialogue and debate. Instead, ideology forces compliance with a set of preformed beliefs. Education becomes a method of indoctrination. Now one must be careful here, because there are sets of true propositions enfolded in these ideologies. The problem is that nothing is up for debate. Questioning the ideology is the same as denial of the ideology, and one becomes excommunicated from the “group think.”

As an educational renewal movement, there is a temptation to offer a counter set of agendas. “Okay, fine,” we might say, “the public schools are promoting the agenda of gender fluidity, then we’ll promote the alternative agenda.” I’m struck, however, that this was not the strategy of DuBois or Washington. Despite racism and segregation, they sought to train students in intellectual and moral skills that would enable them to enter into the discourse of the greater society. Classical Christian schools must avoid the allure of ideological agenda and remain true to training students in the logic and rhetoric that will prepare our graduates to take up nuances positions and speak persuasively from a place of well-developed convictions.

Hand, Head, and Heart

The classical Christian school movement might be more inclined towards the DuBois educational program. He, after all, promotes the very same liberal arts tradition we call home. However, DuBois himself saw the liability of creating an elite class that becomes self-perpetuating; enamored of its own self-importance rather than utilizing its position to raise all of society. Thus, a Washington-DuBois synthesis is well worthy of consideration.

The phrase “hand, head, and heart” comes from Washington. (Up from Slavery 85) This is a valuable triad to frame a fully embodied philosophy of education. I really like this phrasing pulled from the website of the Ecclesial Schools Initiative, “A classical education beckons learners toward goodness, truth, and beauty, wherever it may be found, integrating faith into all areas of learning, and helping students acquire the habits of heart, body, and mind that are essential for living a flourishing human life.” Kevin Clark, founder of the Ecclesial Schools Initiative, is one of the authors—along with Ravi Jain—of The Liberal Arts Tradition (reviewed here). Technical skill is recognized in this book as a “wholly legitimate pursuit.” In other words, we cannot be so singularly focused on the intellectual and moral development of our students that we leave no room for skills development. Clark and Jain write:

“The liberal arts are only intended to be the tools of learning to be used in all other studies. The three branches of philosophy and, in addition, theology, then contain the integrated tapestry of all other knowledge as represented by the innumerable particular sciences, such as biology, ethics, economics, and chemistry. Moreover, professional degrees, to be acquired later, recognize that other skills (arts) are needed for one’s vocation.”

Clark and Jain, The Liberal Arts Tradition, 7

To this might be added apprenticeship in a trade as opposed to professional degrees. More and more the collegiate landscape has become overly expensive relative to its waning value due to the ideological agendas present in higher education. Graduates from classical Christian schools might be better placed in trade apprenticeships or military service. All of this to say that the liberal arts are a necessary element in learning the knowledge and character required to live a flourishing life. That life, though, needs to be embodied in vocations that support and promote flourishing. I highly recommend reading through Jason’s article “Apprenticeship in the Arts” where he explores professions and trades in light of Chris Hall’s Common Arts Education.

Educational Renewal in Light of 1895

The momentous occasion of Washington’s “Atlanta Speech” in 1895 marks a period of reflection and debate over education, particularly between Washington and DuBois. It is striking to note that 1895 was also the year when the first professional American football match was played (Sept. 3), the first automobile race occurred (Nov. 28), and the first moving picture film was shown (Dec. 28). When we consider how much society has been transformed by the onset of these modern artifacts, we can see that a significant aspect of what Washington and DuBois were wrestling with was not just racial in nature, but also pertained to how modernism eroded conceptions of individual character and community cohesion.

The impact of modernism has left us with a society that is fractured and hurting. Hopefully by tracing the debate between Washington and DuBois, we can see lines of constructive thought that invigorate our own educational renewal movement. We have in both Washington and DuBois compatriots who are deeply concerned to cultivate virtue in students for the betterment of society. If Up from Slavery, The Souls of Black Folk or “The Talented Tenth” are not yet in your curriculum, I highly recommend their adoption. Perhaps this review of their work has inspired you to consider ways to broaden your understanding of the outcomes for classical Christian education. Perhaps our students, trained in the liberal arts, are exactly what our society needs to lead us out of our current political catastrophe. Perhaps our students, educated holistically in hand, heart and head, will embody the lives of flourishing that is the true outcome of a good education.

Leave a Reply