In the previous article in this two-part review of Jonathan Pennington’s book Jesus the Great Philosopher, I spelled out the first two sections of his book dealing with the ancient philosophers (chapters 1 and 2) and then the Old and New Testaments (chapters 3 and 4). Here I will dive into the final three sections on emotions, relationships and the flourishing life. In each of these sections, Pennington provides insights that help us understand better the nature of our roles as teachers to educate formationally the students given into our care.

The thesis that emerges through my review is a sense that we are apprenticing students in the craft of living flourishing lives. There are so many points of connection between what Pennington has written and our educational renewal movement. Even though he didn’t write this book solely with our context in mind, it resonates so much that I highly recommend this as one of your must reads in the coming year.

Training the Emotions

It is difficult to get a handle on our emotional lives. Think about how true this is in your own life as a teacher. The vicissitudes of the school day and the school year impact us at an emotional level constantly. If this is true in our own lives, how much more do our students feel a range of different emotions? And yet we rarely consider how much emotional training is part of our job as educators. Pennington does a great job laying out a sophisticated view of emotions from a Christian philosophical perspective.

To begin with, the philosophical discussion surrounding emotions goes all the way back to the ancient philosophers. Plato and Aristotle had significantly different views on our emotions. Plato “saw emotions (or passions) as impulses that come upon us as an uncontrollable force.” (86) His noncognitive understanding of emotions weaves its way through history down to our modern era of chemical and neurological research. Pennington writes, “Even if one doesn’t take an entirely chemical approach to emotions, today emotions are largely viewed as negative and the enemy of sound thinking.” (88) Aristotle saw things very differently, taking an “integrated, cognitive approach.” (89) Our whole being works together. “We feel emotion in our bodies and souls through cognition, through using our minds in dialogue with our bodies.” (89) Now obviously the chemical and neurological insights gained by modern research has contributed to our understanding of numerous factors contributing to both emotions and cognition. But Pennington correctly draws forward and understanding of emotions as something that can be educated. There is a certain amount of control we have over our emotions. Our emotions can be trained.

To what end, though, are we training our emotions? Is it to gain complete detachment from emotional response as modern Stoic philosophy would have it? Emotions or feelings are actually necessary for navigating life successfully, so the kind of training envisioned is not to root out emotions but to feel with understanding. Pennington writes:

“Philosophical reflection and psychological research have also shown that emotions are central to aspects of our lives that we may not immediately recognize – specifically, our ethics and morality. . . . To state it most clearly: Emotions are central to our morality (1) in enabling us to determine what is right and wrong, and (2) as indicators of our moral character. Therefore, paying attention to and educating our emotions is crucial to the Good Life.”

Jonathan T. Pennington, Jesus the Great Philosopher, 95

Our development as integrated beings means bringing together our feeling self, our thinking self and our acting self (emotions, reason and behavior). Pennington posits that Christianity takes a cognitive approach to emotions similar to the Aristotelian tradition. Emotions are fundamentally good in part because they reflect the nature of God who has emotions and is entirely good. (105) As Christians we are called to control our emotions, not simply detach from them. “While promoting the good of emotions, Christianity also recommends a measured and intentional detachment from the world and its circumstances for the sake of living a tranquil life.” (114)

So how does one go about educating the emotions? One of the keys highlighted by Pennington is “the habit of intentional reflection.” (123) He demonstrates through readings in Deuteronomy, the Psalms and Matthew that “This habit of intentional reflection has a shaping effect on the belief, faithfulness, obedience, and thereby emotional health of the Israelites.” (124) Christian virtue, then, relies on training in specific habits to shape our emotional response to God leading toward true happiness.

Training New Citizens

The philosophy of the Good Life involves not only a coherence of one’s own integrated self, but a coherence of relationships with others. The next section in Pennington’s book delves into relationships and once again synthesizes ancient wisdom with the teachings of the Bible. Relationships are a central teaching in the philosophical tradition. (135) Philosphers like Plutarch, Plato, Aristotle and Cicero all see how marriage and families are the bedrock of a good society. Thus for the society as a whole to be well ordered, “the household was to be ordered well.” (139) So as we consider the philosophical tradition as it teaches about relationships, we can see that relationships span the most intimate and the most global arrangements.

Aristotle once again takes center stage. Pennington writes, “Aristotle argues that the end goal of enabling virtuous citizens to flourish must be the evaluative tool for determining which form of government is best.” (143) From this we can gather that the individual and the many live in a dynamic relationship that ought to aim at a singular goal: “the flourishing of virtuous individuals.” This is a challenging proposition in a society that desires individual autonomy while it remains confused about moral virtue. I think this is where classical Christian education can best serve society by training new citizens to understand what it means to live virtuously as individuals and to engage in public discourse about how to promote the wellbeing of all in light of what it means to be a good person.

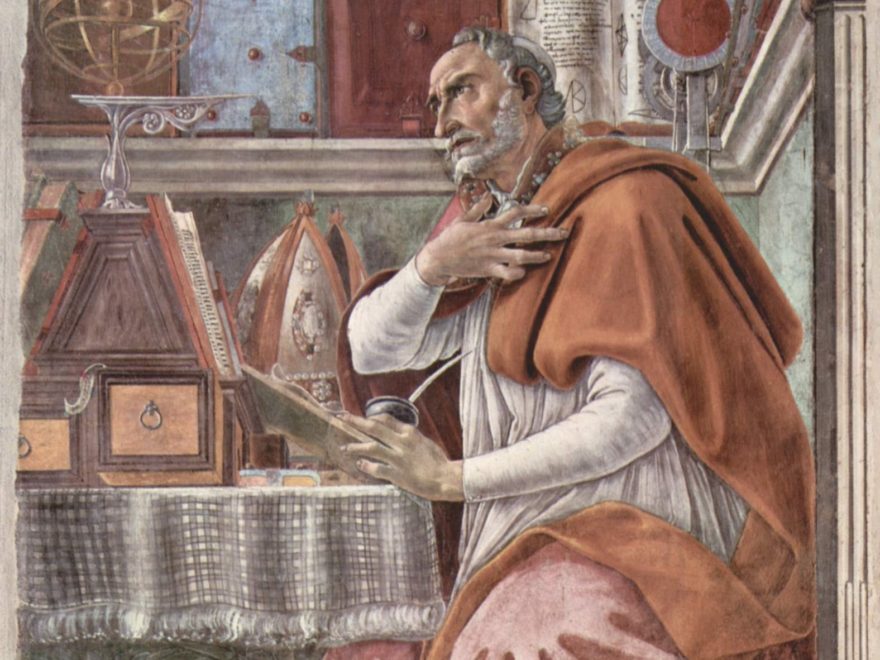

The Bible provides a nuanced perspective, however, on what it means to be a citizen. “Jesus’s life and teaching can fairly be described as a re-forming and renewing of all kinds of relationships – between God and humanity and between humans of every language, ethnicity, gender, and class.” (156) The revelation of God’s divine Word breaks down our understanding of such things as family, friendship and society, and build them up into a new kind of structure centered on Christ Jesus. I think Pennington is most helpful in laying out the fact that the Bible is thoroughly political. What he means by this is that it expresses several nuanced points about a philosophy of politics. For instance, “Christians must understand that they are now citizens of two reams, or two cities, as Augustine would famously describe it – the city of humanity and the city of God.” (166) Our first loyalty is to our citizenship above. We pray fervently that God’s will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Yet, these two realms exist in conflict. As citizens of an earthly realm, we prioritize our heavenly citizenship while also participating in the betterment of our earthly society. “Therefore, the Christian’s relationship to the state is one of respectful participation and honor where honor is due (1 Pet. 2:17), praying for even ungodly leaders (1 Tim. 2:1-4).” (166) Our civic duty is real and earnest because we are emissaries of our Lord Jesus Christ and carry the diplomatic message of the good news of the gospel.

Training up new citizens is a difficult task. Even though our present state of cultural discourse feels overwhelming and dysfunctional, I am certain that this feeling is not unique to our day. As educators, our task is not to teach a number of talking points from whatever political party our constituents agree with. Instead, we are to help our students understand their dual citizenship, learning to walk as Christ walked and working toward the transformation of society in light of the gospel. Pennington puts it well:

“Jesus and the New Testament regularly paint a picture of what the true politeia modeled on God’s kingdom should be. Christian teaching is a vision that resocializes people’s values and habits, that creates a new community of people, a new covenant people who will live together in love and serve as a model for the world of God himself. This is a sophisticated philosophy of relationships.”

Jonathan T. Pennington, Jesus the Great Philosopher, 171

Training in Happiness

One of the claims I persistently make that differentiates our educational renewal movement from conventional education is that we train up students to live lives of meaning and purpose. The factory model of education focuses on technology and techniques that provide for better jobs with the assumption that a highly trained workforce is the chief end of society. But as classical Christian educators, we have a higher vision that transcends career. We believe that educating the whole person entails addressing life’s biggest questions and launching our students into a pursuit of true happiness.

Pennington closes his book with two chapters that align with what makes our movement unique. He demonstrates that “happiness and meaningfulness entail each other” (189) by reviewing ancient and modern philosophers. Our modern world with its largely scientific worldview struggles to provide the kind of comprehensive view of life that produces meaning and purpose. This is why we benefit so much from going back to the great philosophers of the ancient world. They “all pondered the great questions of happiness and offered practical, real-life wisdom on how to live well.” (191) The antidote to our modern malaise comes through intentional reflection on the big questions of life. He writes in summary of the ancient wisdom:

“So they disagreed on lots of habits and beliefs, but they all shared this central idea: We long for flourishing, and the only way to find it is through living intentionally and thoughtfully in particular ways. Neither virtue nor its eventual fruit, happiness, come to us accidentally.”

Jonathan T. Pennington, Jesus the Great Philosopher, 193

The ancient wisdom stands in stark relief with what we might call the self-help industry. We have modern YouTube gurus offering tips and tricks to live better lives. In certain cases, really thoughtful programs synthesize philosophical sophistication with modern science, attempting a nonreligious, “whole-life philosophy of happiness.” (200) But “the gurus that people look to today offer only a limited kind of happiness.” (200) It seems to me that our society reflects the educational norms of conventional education: technology and techniques have soft pedaled a less-than-satisfying philosophy of life.

Pennington’s final chapter masterfully explores Christianity as a superior life philosophy full of meaning that promotes flourishing. He writes, “Jesus in the actual Logos – the organizing principle of the world, the agent of creation, the being that holds the whole universe together – this means that his philosophy alone is whole, complete, and truly true.” (201) Two key words stand out in Pennington’s exposition of Christian philosophy: grace and hope. Despite the fall and despite the limitations we face as human beings, God’s grace is poured out on humanity in the form of wisdom. We are recipients of divine wisdom: not only what we might call special revelation, but the wisdom that permeates all creation. “Any wisdom in the world is from God who created all.” (203) Together God’s creation and God’s Word provide answers to life’s greatest questions. This is grace.

Hope is perhaps the single greatest factor when comparing the self-help philosophy of today with the whole-life philosophy of the Bible. Pennington writes:

“The Christian hope is that God is going to return to restore the world to right, to bring light into darkness, to create a new creation of shalom and peace, to be present fact-to-face with his creatures. It is this hope alone that can bridge the eudaimonia gap between our experience now and our deepest longings.” (216)

To understand what he means here, it is helpful to consider the eudaimonia gap. All humans desire to experience happiness or eudaimonia. However, we face a world of suffering, whether it be physical, mental, relational or otherwise. The gap we experience between the happiness we want to achieve and the reality of the obstacles that interfere with us experiencing that happiness is what we might call the eudaimonia gap. Christianity offers a satisfying solution by presenting us with a future hope. “Christian philosophy emphasizes precisely this – an honest assessment of the brokenness of life that is always oriented toward a sure hope for God’s restoration of true flourishing to the world.” (218) Christian hope is not a detachment from the problems in our world nor does it trivialize suffering. Instead, Christian hope finds profound meaning in this life through the recognition that suffering and pain are where God meets us as he leads us toward eudaimonia.

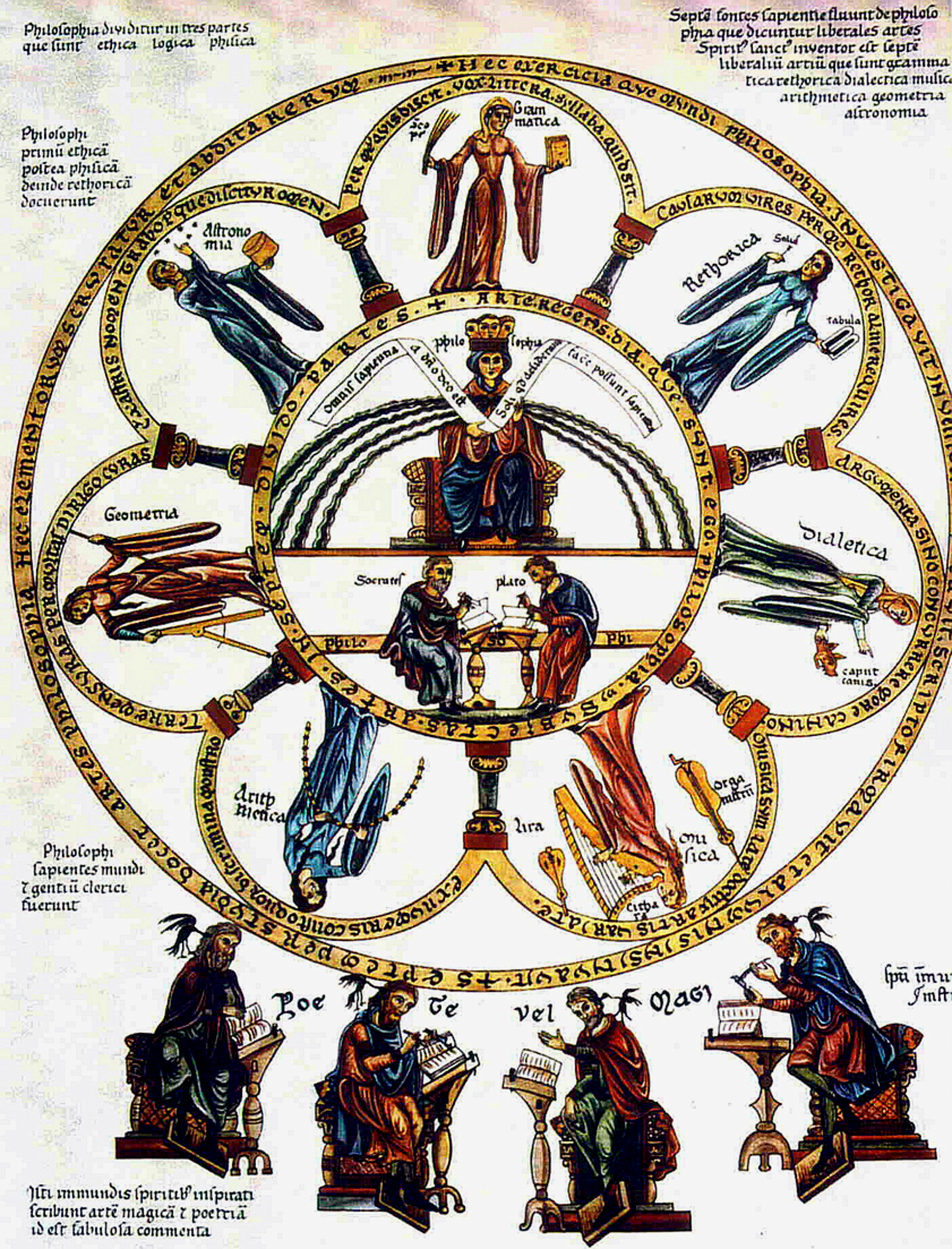

This review of Pennington’s book Jesus the Great Philosopher has hopefully stimulated your thoughts on what it means to be a classical Christian educator. A book like this helps contextualize daily classroom life with the long view of living the Good Life. In the liberal arts tradition, discrete subjects (if that is even the correct word) cohere around philosophy. So when we are teaching mathematics, literature or science, we should have in view that the subject matter is not limited to one domain of knowledge. Education is a science of relations, as Charlotte Mason has so famously put it. Pennington’s book serves as a convenient and accessible manual for bringing into conversation the liberal arts and a biblical worldview. I highly recommend you reading this for yourself to be inspired as a classical Christian educator.

Beyond this, I could see this book being adopted in a theology or humanities class at your school. The way he brings the many streams of wisdom together will benefit students who have had many years of tutelage under the writings of Aristotle, Augustine, Lewis and many others. Even if you don’t bring this into your curriculum, I could see this being a great read in a book club, contributing to lively discussion and thoughtful interaction.

Leave a Reply