In the first two posts of this series (which I am reviving after a 6 months long hiatus) I proposed replacing Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives with Aristotle’s intellectual virtues. The major flaw in Bloom’s taxonomy, which is a hierarchical categorization of educational goals in the cognitive domain, is that it privileges the bare intellect over the heart, like so much of modern education. Even if Bloom and his university examiner colleagues proposed an affective and psychomotor domain as well, and had the modest goal of improving clarity and communication among teachers, curriculum planners and educational researchers, still they codified the modern academic system’s focus on intellectual abilities and skills alone. In doing so they divorced the head from the heart and body in a way that makes it hard for even classical educators today to fully recover. We all breathe in this educational air, and walk through these educational halls, with Bloom’s built into the very architecture.

But it is important to acknowledge the value of Bloom’s project, especially in contrast to the rampant postmodernism that has swept through education since (see 2nd post). The benefit of Bloom’s taxonomy lies in its recognition of the need for clear targets. Without knowing where we are aiming at in education, we are like Alice wandering in wonderland with no sense of where she wants to go. We may get somewhere, but not likely to the true destination of education.

Bloom’s taxonomy may be reductionistic, but at least it lays out and defines a clear set of goals that educators might pursue. Modernism thus has a leg up on post-modernism, in that the house swept clean of all overarching values and metanarratives (except rampant individualism), then becomes subject to the seven demons more wicked than itself that our Lord spoke of. The clean house at least looks nice and could be used by different sorts of inhabitants in the future. But this analogy may seem to strike a more ominous note against postmodern education than I intend. Simply put, when clarity is away, ideologies come out to play.

In a way then, our critique of Bloom’s project is a simple one: Benjamin Bloom and his colleagues should not have simply taken modern educators’ own language as their starting point for their taxonomy of educational objectives.

They state this explicitly in Bloom et al., Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals, Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain (Ann Arbor, Michigan: David McKay Co., 1956), 6:

Insofar as possible, the boundaries between categories should be closely related to the distinctions teachers make in planning curricula or in choosing learning situations. It is possible that teachers make distinctions which psychologists would not make in classifying or studying human behavior. However, if one of the major values of the taxonomy is in the improvement of communication among educators, then educational distinctions should be given major consideration.

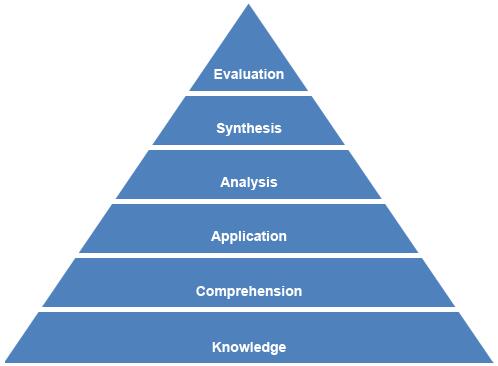

Even if their taxonomy brought clarity, definitions and examples to the teaching and testing process, they relied on the average American teacher or examiner’s assumptions about what education was all about. Instead of recovering the best of the liberal arts tradition on the nature of the mind, virtue and wisdom, they solidified a lowest common denominator philosophy of education. Teachers and curriculum writers are mostly talking abstractly about knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation, so we’ll detail and define those, provide some examples of examination questions and call that education. They justified this questionable move by modelling their project on the hard sciences and appealing to the philosophical pragmatism that had come to dominate educational philosophy in America.

Perhaps the greatest irony in their approach is that they thereby furthered the divide between education and life. Classical education may sometimes be critiqued as an ivory-tower intellectual exercise, but its traditional focus on virtue, wisdom and the good life puts the lie to this claim. The liberal arts too are eminently practical, if we understand the word ‘practical’ appropriately. What could be more helpful in life than the ability to read, reason, persuade, calculate, chart, navigate and sing?

Aside: This list of activities might seem like a reductionistic vision of the seven liberal arts, but I do not intend it that way. Instead I am attempting to reinstate the classical distinction between ‘art’ and ‘science’, recognizing Aristotle’s and others’ emphasis on arts as activities producing something in the world. I have for some time been envisioning a project that would look at the seeds of the liberal arts to recover their practical origins and purposes (working title = Free to Serve: Rediscovering the Liberal Arts as Practical Tools, coming once I have the time to devote to it).

Modern education in the tradition of Bloom’s, on the other hand, is the real culprit, abstracted as it is from a proper relationship not only to the working world, but also to a moral and communal life. Education becomes about preparing to perform on a modern standardized test, regardless of the ensuing life of the individual who either fails, passes with flying colors or is confirmed in mediocrity.

So then, we can break down the bad of Bloom’s under two headings: 1) its scientistic philosophy obsessed with objectivity and measurability, and 2) its social scientific focus on neutrality, rather than a holistic embrace of traditional moral philosophy.

Bloom’s Scientism: Objectivity and Measurability

In a way we should hardly be surprised at the scientism of Bloom’s taxonomy. After all, the idea of a taxonomy itself was borrowed from the biological sciences, acting as a vivid signpost of the larger project that so many in education and other “social sciences” found themselves swept up by during that era: to reframe the subdisciplines of traditional moral philosophy on analogy with the wildly successful hard sciences. Understood under this heading, the opening sentences of the foreword come sharply into focus:

Most readers will have heard of the biological taxonomies which permit classification into such categories as phyllum, class, order, family, genus, species, variety. Biologists have found their taxonomy markedly helpful as a means of insuring accuracy of communication about their science and as a means of understanding the organization and interrelation of the various parts of the animal and plant world. You are reading about an attempt to build a taxonomy of educational objectives. It is intended to provide for classification of the goals of our educational system. It is expected to be of general help to all teachers, administrators, professional specialists, and research workers who deal with curricular and evaluation problems. It is especially intended to help them discuss these problems with greater precision.

Bloom et al., Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, 1.

I am not in any way retracting my praise of the value of clarity, when I remark that Bloom’s project relies on a false analogy between education and biology. Our educational goals may not, in fact, organize themselves neatly into a manageable number of orders and species, if we only provide clear definitions. Aristotle himself might have observed that such a discussion

“will be adequate if it has as much clearness as the subject-matter admits of; for precision is not to be sought for alike in all discussions, any more than in all the products of the crafts.”

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics Book 1, Ch. 3, 1094b.12ff., in The Complete Works of Aristotle, vol. 2, The Revised Oxford Translation, ed. By Jonathan Barnes (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 1730.

It may be that the real objectives of the craft of education cannot be so precisely distinguished and classified, let alone tested, without some damage being done to the nature of the subject itself.

We can imagine Benjamin Bloom and his fellow committee members, who were all college and university examiners, as well as the many educators who participated in the conferences from 1949-1953 that helped develop the taxonomy, being attracted by the idea of a taxonomy of educational goals tested by their examinations. Perhaps by classifying and standardizing terminology, they might have thought, we can do away with the subjectivity of all these K-12 schools and their teachers. Perhaps we can finally make our tests objective and do away with the immeasurable criteria by relegating it to the affective domain, which we can tip our hats to as valuable, while functionally ignoring it as subjective and too fraught with controversy.

I would not press my imputation of their motives too far, but there seems to be legitimate indications in this direction in their statements about their “progress” in the affective domain, Bloom et al., Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, 7:

A second part of the taxonomy is the affective domain. It includes objectives which describe changes in interest, attitudes, and values, and the development of appreciations and adequate adjustment. Much of our meeting time has been devoted to attempts at classifying objectives under this domain. It has been a difficult task which is still far from complete. Several problems make it so difficult. Objectives in this domain are not stated very precisely; and, in fact, teachers do not appear to be very clear about the learning experiences which are appropriate to these objectives. It is difficult to describe the behaviors appropriate to these objectives since the internal or covert feelings and emotions are as significant for this domain as are the overt behavioral manifestations. Then, too, our testing procedures for the affective domain are still in the most primitive stages. We hope to complete the task but are not able to predict a publication date.

It may be that our authors express this hope with the utmost sincerity, but they have framed the task with such “difficulties” and in such a way as to make meeting their requirements all but impossible, because of not accepting the level of precision that the subject-matter properly admits of (contra Aristotle).

After all, these college examiners would likely have been temperamentally inclined to providing greater precision, just as they would have been socially pressured to model their social science after the hard sciences in the middle of the 20th century.

In a way, Bloom’s taxonomy is simply the dictum of Galileo Galilei as applied to testable goals in education: “Measure what is measurable, and make measurable what is not so.” In Galileo’s defense, he probably did not envision the cannibalization of moral philosophy by the sciences. We should be careful again to affirm the value of measuring more in “social sciences” like education, psychology, and politics, than we had done in earlier eras. Measurements, like the abstract grading system commonly used in contemporary education, have almost certainly improved some things, but they have also had their share of negative effects—an observation that I hardly have to argue for, given the testimony of the countless parents of anxious or disengaged teenagers.

Social Sciences vs. Moral Philosophy

But what really is the problem with the social sciences approach vis-a-vis traditional moral philosophy? Kevin Clark and Ravi Jain break this development down admirably in The Liberal Arts Tradition: A Philosophy of Christian Classical Education (version 2.0):

The methodologies of the contemporary social sciences implicitly critique traditional moral philosophy by suggesting it relies on assumptions about human nature and human purpose that are not rationally or empirically verifiable. They have reduced the sphere of moral philosophy to the isolated study of ethics, dissociated from the social sciences. This can only be effectively argued for when reason itself is truncated. Reason is truncated in the sciences when it is only allowed to consider efficient or material causation (simple cause and effect or material composition). By doing this, reason is made to ignore key aspects of moral reasoning such as explorations of meaning and purpose (formal and final cause). Instead these aspects of reason are now condemned as irrational because they involve judgments made by communities of tradition and faith. (132)

Aristotle’s willingness to ask philosophical questions about the meaning and purpose of human beings, just as of animals or man-made objects like tables and chairs, stands in stark contrast with Bloom and his colleagues, whose decided preference is for a veneer of neutrality, objectivity and pragmatism. This is part of why I am proposing the replacement of Bloom’s taxonomy with Aristotle’s intellectual virtues, as primary goals of education. Because with Aristotle, at least, the intellectual virtues find themselves within a committed philosophical system that, even if imperfect, has been harmonized fruitfully with Christian fundamental principles before. (Aquinas comes to mind, amidst a whole tradition.)

Bloom, on the other hand, is content to punt on questions of meaning and value, the ultimate purpose of human beings and therefore of education itself. Human values and schools of educational philosophy can be safely avoided to gain widespread acceptance of a secular public discipline. As they freely admit in their foreword:

It was further agreed that in constructing the taxonomy every effort should be made to avoid value judgments about objectives and behaviors. Neutrality with respect to educational principles and philosophies was to be achieved by constructing a system which, insofar as it was possible, would permit the inclusion of objectives from all educational orientations. (6-7)

The house must be swept clean of non-objective, non-scientific value judgments, so that anyone can use it. Such a plan of attack is perfectly comprehensible for modern secularists (on their way to embracing pluralism). I am hardly criticizing their vantage point, given their worldview. But for contemporary Christians who embrace the tradition of moral philosophy, not to mention a classical philosophy of education, it certainly leaves something wanting.

What after all is education really about? Mere training in intellectual abilities and skills? Or is human flourishing, moral virtue, wisdom for life, or even a relationship with the Creator God a proper goal? And what if such things cannot be easily measured? Should we therefore abandon them? Or perhaps, if we truly followed Galileo’s dictum, we would advance and not retreat. Perhaps we should work harder to make these goals measurable, even if we accept that such measurements might not be as precise as some others. That is the goal of this project. Advance into the fray of making measurable what truly matters in education.

Leave a Reply